To this day, the fanatic fan-boyism for Muhammed Ali is as myopic as ever. The Narrative on Ali is always him overcoming adversity and bigotry to beat the odds and show the world he was “The Greatest.”

While one has to admire his footwork, his lateral movement, his masterful head games, and his ability to absorb punishment to the body, you must use selective metrics to determine he was ‘the greatest”…or even the greatest heavyweight. What he conclusively proved is that, at least in his younger days, he could move faster backwards than his opponents could move forward.

Nobody before Gaseous Cassius had so brazenly flaunted such raw egotism. Humility was still a virtue before Cassius Clay’s ascendance. Now all athletes (and most people in general) are arrogant, trash-talking legends in their own minds. Clay/Ali was the trailblazer for grandiose, egomaniacal personalities in sports.

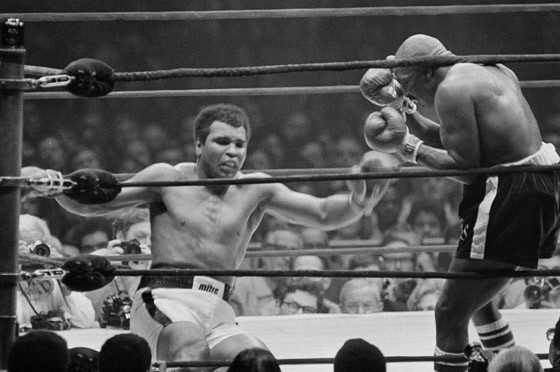

In this bout, Ali probably thought he could use the rope-a-dope strategy as he did in Zaire, and cause Shavers to punch himself out. There turned out to be two problems with that plan: the ropes weren’t nearly as loose as they were in Zaire; and Shavers had learned from that particular George Foreman blunder. Although Shavers had a small gas tank (like a lot of power punchers), he showed remarkable discipline in pacing himself, for the most part.

Arguably, Shavers was far too cautious. He ignored multiple opportunities after stunning Ali with hard shots, and had him hurt more than once, but failed to follow up effectively. Unbelievably, Ali even backed into the corner on several occasions. This would have been a suicidal tactic against a fine-tuned Mike Tyson, or The Rock at any time. (Marciano would pound on whatever part of an opponent’s body could be reached. If the best target he had was the arms, he would bang them until they couldn’t be lifted for protection any longer.) But Shavers only made token efforts at punching in these circumstances. Every such opportunity ended by Ali clinching, or Shavers simply backing away to let him off the hook.

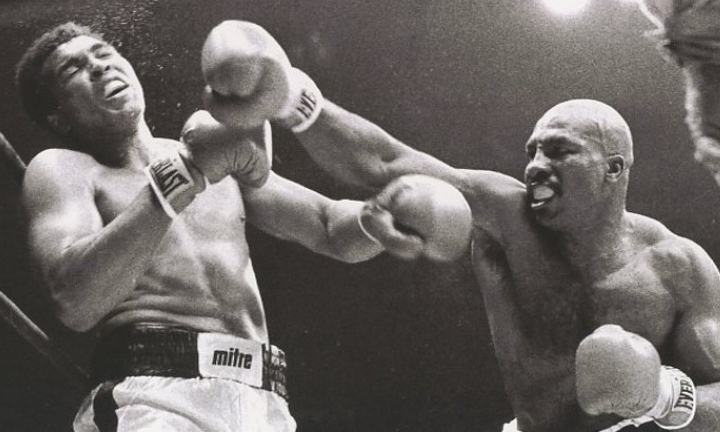

A fight historian can probably count on one hand the number of times the elusive Ali was ever hit flush. Three of those times, he went down. Shavers never caught him flush, but even glancing blows from Shavers nearly took Ali’s head off. Starting in the fifth round (and intermittent thereafter), Ali jumped on his “bicycle” to evade Shavers, offering an occasional feather-fisted counterattack.

As in too many fights throughout history, only a knockout could have overcome the favorite’s “home cooking” in this bout. As was typical in Ali’s reign, the referee allowed him to hold and hit for all 15 rounds, with only one warning. Because he could get away with it as usual, Ali clutched the back of Shavers’ head with one glove any time Shavers got inside. Shavers was the aggressor from bell to bell, landing the most effective punches consistently, unfazed by Ali’s occasional attempts at offense right up until an adrenaline-fueled flurry in the last seconds of the fight. No fair, impartial judge would have awarded the champion more than five rounds…but the judges were, like the referee, effectively part of Team Ali. All of them scored the fight an astonishing nine rounds to six in favor of the guy who got battered around the ring like Michael Avenatti’s girlfriend.

Shavers fought less than a perfect fight, to be sure. And maybe his excessive caution was partially warranted–he seemed to be out of gas by the end of Round 15 (possibly because, despite his caution, he still tended to load up and swing wild Western Union punches when he got excited). He was hardly the first to be exhausted from chasing the Louisville Lip around all night. Considering the officiating and scoring he was up against, his only path to victory was a knockout. He had Ali in deeper trouble, far more frequently, than Foreman ever did. It would have been fascinating to find out what might have happened, had Shavers not squandered so many opportunities.