The next day, Uncle Si informed me that my training would resume. It was more important than ever now, he said, since the Erasers were after me.

But first, he gave me a tour of the Orange Grove.

“You ever think about how we have electricity out here?” he asked.

I shook my head. “Not really.”

He nodded. “Of course not. In your time, everybody in America has electricity—even out in the boonies. But there’s no power company that has lines out this far, where and when we are right now.”

He took me to what looked like a tall, sturdy barn. Once inside the blazing hot structure. I saw that it had no roof. It was not a barn at all, but a disguise. Inside the walls was something like a green house, with a slot recessed into the floor, full of water. Sitting in that pool, but with the top sticking up out of the greenhouse, was a gigantic wheel, slowly rotating through the opening of the structure. The wheel was a circle of metal tanks, all connected by spoke-like pipes deflecting around a central hub. The hub drove an axle which also protruded from the greenhouse (horizontally, in this case) and into a gearbox which, in turn, drove a large circular mechanism.

Uncle Si pointed to this last component. “That’s the alternator. Don’t get too close; it puts out enough current to fry you to a crisp.” Then he waved to the big wheel. “That is a Temperature Wheel. Not very fast, but massive torque. Each tank contains a gas with a very low boiling point, and they’re all interconnected. It’s sunny just about all year ’round, here. The sun heats the pool, which heats the tanks that are in the pool. The gas expands, pushing through the pipes into the tanks that are up in the breeze–but under shade. There the gas cools down, settles as liquid, making the tanks on top heavier, and gravity pushes them back down.”

“…So the wheel spins,” I finished.

“I get enough juice to power everything here, and it costs almost nothing,” he said.

“Almost?” I repeated. “Looks completely free to me. You don’t have to pay for the sun, or the air. The water doesn’t get used up; and neither does the gas in the wheel.”

“But it did cost me something to build it,” he said. “And it does require occasional maintenance.”

“Oh, yeah.”

He pointed to the inner walls of the pseudo-barn. They were lined with heavy shelves which held large, solid-looking boxes all connected by thick, insulated cables. “For the occasional cold spells when I don’t get at least a 3.5 degree difference in temperature between the air above the greenhouse and the water in the pool, I’ve got a network of battery banks, to keep the property powered.”

“Those are batteries?” I asked, staring at the huge, dark casings. They were enormous compared to car batteries.

He nodded. “Nickel-iron. They’ll last forever and take plenty of abuse. Slow discharge, but with nearly unlimited cycling. Just about perfect for this place.”

Several huge concave mirrors were placed up high inside the walls of the open-top barn, reflecting extra sunlight into the greenhouse.

I stared at the huge, slow-turning wheel. “This is something else.”

“It’s crude technology,” he said, dismissively. “Since putting this together, I’ve stumbled on some mind-blowing stuff. But anyway: like with any of the goodies I have around here, you can’t ever tell anyone about it. Savvy?”

I hadn’t heard the term “savvy” before meeting Uncle Si, but deduced from context he was asking if I understood. “I won’t tell anybody anything.”

He nodded, then continued the tour.

He opened a big, up-swinging door on the other side of the hangar, and I discovered that there were airplanes there, after all. He climbed in one and started it. Twin propellers spun into a blur. He steered it out of the hangar and got out to shut and lock the hangar door.

I couldn’t remember ever seeing a prop plane in real life before. This plane was like nothing I’d ever seen—even in old movies. The windows were tinted such that I couldn’t see anything inside. The contours were sleek and swoopy, like so many other manufactured objects in this era. But still, it looked like something out of a 1930s cartoon, more than a 1930s airport.

“Get in,” he said.

He climbed in and out, checking his lights and other components. By the time he was done, the engines were warmed up and ready to go. He taxied around to an air field cut out of the sprawling grove.

“Is this plane from 1934?” I asked, once strapped into the co-pilot’s seat, scanning over some real sophisticated, high-tech-looking instrumentation around the cockpit.

“Nope,” he said. “It’s a one-off custom. I had it built to look like something that belongs in the age of art deco, but not even an aircraft buff could place this baby.”

I halfway expected him to slip on a radio headset, but he didn’t. He throttled up the engines, released the brakes, and we sped down the runway. The plane lifted off smoothly, and picked up speed as it climbed at a shallow angle.

Uncle Si fiddled with one of the instruments, and I was wracked by the same phenomenon I experienced in the badass car a week ago: my stomach free-floated; vision and hearing went haywire; then everything came roaring back to normal.

Normal except the airplane was flying over a totally different landscape, now.

The plane leveled off, then began a shallow descent. Ahead and below I saw another air field, with crisscrossing runways, hangars and other buildings , hacked out of a jungle between three mountain peaks. Uncle Si did put on a radio headset, now, and engaged somebody in a short conversation I didn’t follow.

“Where are we?” I asked, once he was done.

“BH Station,” he said, without looking away from the windshield. “One of my most advanced, extensive bases. The rain forest thins out a bit up here, but unless you know what you’re looking for and where to look, it’s the proverbial needle in a haystack.”

Ever since meeting Uncle Si, my vocabulary had been expanding. On my next session with a dictionary, I would have to look up “proverbial” and “art deco.”

The sights below stretched out from a map-like image to life-sized reality—surrounded by the dark green carpet of jungle extending to the horizons. I couldn’t tear my eyes away from the transition of scale.

The runway grew underneath us until we could touch it. The landing was nearly as smooth as the takeoff. Then we taxied toward a long row of speed-bump-shaped metal buildings.

As we drew closer to one particular hangar in the midst of the row, it became obvious how enormous the structures were. They were painted to blend in with the surrounding countryside, and so hadn’t been noticeable from higher altitudes.

A man in greasy overalls ran past us to open the hangar doors, and Uncle Si stopped the plane to wait. I shifted my gaze from the front to below. My eyes were caught by something shiny in the pavement under us. It was a piece of metal—maybe from an old soda can pull-tab or something—which had evidently gotten mixed up in the asphalt somehow. Had we been 20 feet farther away in any direction, I never would have noticed it. It was only because I was on top of it that I even knew it existed. It seemed odd enough as to serve as a good landmark, but after the hangar doors were open and the plane began moving again, it disappeared into the texture of the tarmac. I could no more locate it now than I could before I knew it was there.

I didn’t ponder the contrast of microcosm to macrocosm very long, though, because of what I saw inside the hangar. There was a collection of aircraft (both jet and propeller) that belonged in a museum—everything from futuristic to antiquated.

Uncle Si disembarked and I followed him out of the plane into the hangar. The air was heavy, hot, and sticky. I began sweating almost immediately. But I stared at the other planes.

“What’s in all the other hangars?” I asked.

“Some of them are still empty,” he said, shrugging. “Most have other aircraft. This is the hangar for twin engine passenger planes.”

“Different vintages so you can visit different times?” I asked.

He grinned, but touched his index finger to his lips briefly. “Shh.”

The man in greasy overalls arrived. Uncle Si shook hands with him, asking, “How’s it going with the VTOL?”

“Still got some tweakin’ to do. But fuel consumption is down about four percent.”

Uncle Si frowned. “I was hoping for more than that.”

The man looked at me curiously.

“Sprout, this is one of my mechanics: Frank. Frank, this is…you can call him Sprout, for now.”

Frank nodded at me…a cursory jerk of the head…and turned his attention back to my uncle. Not a very friendly guy; or at least not all that interested in me. They walked and talked, and I followed.

Their discussion sounded technical, with too many words and acronyms I didn’t understand. Outside, Frank slid the hangar door shut and locked it. He walked away by himself. Uncle Si led me to a control tower.

“Um, Uncle Si? Who owns this airport?”

Without looking at me or breaking stride, he said, “I do,” as if it were a silly question.

Beyond the air strip, out around the fenced perimeter, I noticed men in green uniforms and mirror-like sunglasses walking routes, brandishing weapons.

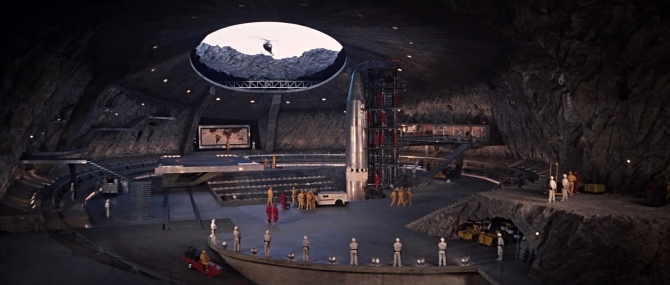

My uncle is a James Bond villain!

After unlocking the steel door at the base of the tower, Si led me inside and locked the door behind us. He sure was security-conscious. There was a metal staircase leading up, but instead of climbing it, he turned to a chain-link cage with a warning sign that read: “DANGER! HIGH VOLTAGE—KEEP OUT.” In the same font but some other language, it spelled out what I assumed was the same notice.

Ignoring the sign, Uncle Si unlocked the gate on the cage and opened it. Inside the cage was a large steel casing with more high voltage warnings, humming like a power transformer. He unlocked the casing and swung it open. Inside, of course, I expected to see some kind of control panel with buttons, switches, and gauges. Instead, there was a metal ladder extending down.

He sent me down the ladder while he locked up behind us. I reached an underground floor at the bottom of the ladder and looked around. I was in a small, hexagonal chamber with heavy vault doors on six sides. The temperature was much cooler down here, thankfully. Uncle Si joined me, placed his hand against a scanner on one door, pushed his face against an eyepiece, and the door popped ajar with a thunk. We walked through.

Down a gray concrete-lined corridor, we came to an enormous gymnasium that made The Warrior’s Lair look shabby by comparison.

A few pairs of men were sparring. Others were working the bags, stretching, practicing techniques, and all the other activities I’d grown used to.

Uncle Si turned to me, pointing to a locker against one wall. “You’ll find some work-out clothes that fit you over there. You’ve had a week to rest and goof off, but now it’s time to get back at it. The next couple days will be an evaluation to see how sharp you are. If you haven’t lost much, we’ll start adding to your skills again after that.”

A thin, dark man in a traditional white martial arts outfit left one of the sparring pairs and bowed to Uncle Si, who bowed back. They conversed in a language that sounded similar to Spanish, then they both looked at me.

“I’m too busy to stay down here for the duration of your daily training,” Uncle Si said, “but I’ll be checking on you regularly. This is Paulo. He’ll be your primary trainer, now. Pay attention to anything he tells you. For the most part, your routine will be the same one we’ve established. But he’s going to teach you some new stuff to add, now and then.”

I had a thousand questions, but it was reassuring to know that my training would continue.

***

I hadn’t collected any rust in the previous week. My movement was still solid, and I worked the bags with familiarity. Paulo only spoke broken English, and he didn’t seem the type to pat someone on the back, but I caught him nodding every now and then. Without words of encouragement (in fact, with hardly any words at all except when I needed correction), the old me would have been miserable under this training regimen. But something had already started changing inside me. I didn’t need as much encouragement as I would have required before Uncle Si came into my life. Now, even when I made a mistake, I nonetheless had a glimmer of hope in my core that I was a human being with value anyway, and would continue to improve.

At nights and at dawn, when the air outside had cooled off, I did my roadwork around the inside of the perimeter. The armed guards soon got used to me passing them on their beats. I would gaze up in wonder at the strange constellations in the night sky as I ran. Inside, before training with Paulo each day, I had to concentrate on conditioning. That included circuit drills, monkey bars, rope climbing, wind sprints, etc.

Aside from roadwork, and my three hours of training a day, Uncle Si let me have the run of the place.

BH Station (Brazilian Highlands Station, that is) had a small city concealed underground—all connected by concrete-lined tunnels and catacombs. It might have been the ultimate dream playground for any young boy with an imagination.

The power source wasn’t explained to me (and I probably wouldn’t have understood it at that point in my life, even if somebody tried) but Uncle Si did mention that it was far more efficient than the Temperature Wheel back at the Orange Grove. I did meet a man he introduced as an engineer, though, who evidently designed BH Station’s power plant, and spent most of his time working on stuff that was even more important. His name was Dr. Torstenson. I think he was Norwegian, though he wasn’t interested in telling me about Vikings—and didn’t seem to know much about them, or Norse mythology.

There was a library full of books and computers; a sprawling recreation area with raquetball courts, a swimming pool, video arcade and the coolest go-cart track ever (for electric carts that could really move); barracks for the guards; a cafeteria; a laundromat; commissary; motor pool; several laboratories; individual quarters for other people who lived there; and Uncle Si’s suite which included bedrooms, private kitchen and bathrooms, living room and the works. My palm print and retina scan was added to the security database so that I had access to most of the facilities in the complex, and several of the entries/exits.

There were guards; electricians; mechanics; engineers and assistants; pilots and drivers who lived there. There were also maids, cooks, dishwashers, nurses, and other women whose job descriptions I didn’t know.

One woman in particular lived in Uncle Si’s suite. In retrospect, Carmen was not only beautiful, but the Brazilian lady was classy, sweet, and generous. I couldn’t recognize any of that for some time, out of an instinctive loyalty to Mami. As much as I admired Uncle Si, his double life in different time-space coordinates struck me as a betrayal of the woman I loved like a mother.

Uncle Si flew in and out of BH Station at least once a day. He wasn’t gone for long…relative to my fixed perspective. But he used a variety of different aircraft, and on some occasions, left in a land-bound motor vehicle on a winding mountain road leading away from the complex.

One of my first nights there I had a nightmare about the Erasing of my mother and half-brother. It woke me up and I couldn’t get back to sleep right away. I took a walk around the complex, and heard something going on in the gym. Curious, but cautious, I snuck up to take a peak.

Uncle Si was in there by himself, working out like a man possessed. Did he do this every night when everyone else was asleep? He wore shorts and knee braces. His sunglasses were gone and his shirt was off. I wondered if I’d ever have muscles like his. Then I glimpsed his back. Most of it was covered by what looked like an awful burn scar.

I wondered how he might have got that scar. Maybe in the car accident that put him in a coma? It must have hurt bad.

There was still an awful lot I didn’t know about my uncle. What I did know was that I wanted to be like him when I grew up.

***

Although there were residents of BH Station from other countries, most were Brazilian. They spoke a dialect of Portuguese, which I couldn’t speak or understand. Nevertheless, Uncle Si warned me sternly not to discuss time travel with anybody. To me, that meant they didn’t know anything about dimensional warps and he wanted to keep it that way. Still, I kind of suspected Dr. Torstenson and some other engineers had at least some inkling.

Working beside my uncle, I overhauled my first engine in the underground motorpool. It was a small one…a V-twin motorcycle engine to be exact…but it introduced me to how internal combustion works. I would continue to build on that little seed of mechanical knowledge throughout my life. It also taught me the importance of math, which he insisted I study for a half hour a day.

He limited my time in the recreation center, requiring that I spend time each day in the library. He welcomed me to learn about any subject that interested me, but frequently emphasized the importance of knowing history.

Having never been much of a student, an assumption common to me and everyone I knew was that I had no aptitude for school learning. Somehow, Uncle Si knew better. It turns out I had a voracious appetite for knowledge. I was already anachronistic at coordinates like this in that I enjoyed reading, so it should have been no surprise that once I got my nose into the sagas of Ragnar Lothbruk, I couldn’t stop until I’d devoured all of them.

At BH Station, people were addicted to “smartphones”—little handheld devices that could perform computer functions as well as make telephone calls via radio waves—but I preferred books and full-sized computers.

From the Norse sagas I went on to research Atila; Alaric I; El Cid, Charlemagne, Harold Hardrada; William the Conqueror; Genghis Khan; Tamerlane; Saladin; William Marshal; Napoleon Bonaparte; Robert E. Lee; Carl Von Clausewitz and Helmuth Von Moltke.

Reading about all those historic warriors, generals and kings kept the concept of leadership toward the forefront of my thinking. The historical events surrounding those figures piqued my curiosity enough to read about the world wars, and that led me to research weapons. I already had an interest in lances, flails, pikes, etc., and looked forward to the day Uncle Si would teach me how to use swords and other melee weapons. Now, through my research, I learned the difference between rifles, submachineguns and machineguns; cannons, howitzers and mortars; infantry, cavalry and artillery.

(The guards who walked the perimeter at BH Station carried rifles, while the roving guards among the buildings carried either shotguns or submachineguns. All of them wore sunglasses, like Uncle Si’s.)

It turns out, by living this way, I received an education superior to anything an institution could have taught me in between their attempts to tame, socialize, and foment ideological conformity.

In time, I grew brave enough to ask Uncle Si to elaborate on what he’d told me about leadership. I asked him specifically about the characters in The Lost Patrol.

In quite a few of the big, modern properties Uncle Si owned, he had his own little movie theaters. He took me into the one at BH Station and we watched The Lost Patrol again. He commented on what characters said and did, and asked me questions. This would become a ritual of ours, and he seemed to enjoy it as much as I did: we would watch movies that depicted groups of people, whether in a military unit, on a sports team, in an office, or any other scenario that might require people to work together. We’d watch them twice. On the second screening, he would point out certain characters he called “real life,” and others he claimed were “total bullshit.” He gave them letter grades on how they handled different situations.

He went into more detail about the Ziggurat. On the top were who he called the Big Dogs. Whether they actually made good leaders or not, they almost always wound up in leadership because others were willing to follow them. Their confidence was such that they not only believed themselves to always be the best man to lead, they effortlessly made others believe it, too. He used Douglas MacArthur, Joe Namath and Vince Lombardi as examples.

The next step down the Ziggurat were the Lieutenants. They shared some qualities with the Big Dogs (like leadership potential) but were willing to follow and make the Big Dog look great by doing a good job with whatever authority was delegated to them. They not only felt protective of the Big Dog they served (until ready to become a Big Dog themselves), but protective of the Ziggurat itself. Like Omar Bradley, Sir Lancelot, Bart Starr, or Al Capone’s top henchmen.

On the middle steps of the Ziggurat were the Worker Drones. They didn’t get the best salaries, the best women, or much in the way of recognition; but were the backbone of pretty much any successful organization. They made it work. They were the offensive linemen. The defensive backs and special teams players. The infantrymen. The engineers and maintenance men. The truckdrivers, mechanics, and railroaders.

On the bottom steps were the Creeps. They resented their low position and thought they deserved better, but were lousy climbers. They could never get to the top unless somebody put them there—and then would do a lousy job. They were passive-aggressive cowards and liars; but embraced the delusion that they were superior to everyone else. They saw themselves as secret Big Dogs-in-waiting but nobody else did—especially women above Tier Six or so. The Creeps’ efforts with women were buffoonish and cringe-worthy; and the harder they tried, the more repulsive they were. They were the desperate salesmen, the pervy college professors, psychiatrists and grandiose comic book villains (“The fools wouldn’t listen to me, but I’ll show them! When my master plan is complete, they’ll all bow before the throne of the All-Powerful Doctor Creep!”)

There were two categories of men who existed independent of the Ziggurat. Dad called one the “Lepers.” Lepers were underneath the Ziggurat. They weren’t just socially awkward like the Creeps; they were socially non-existent. They were the nobodies who were nameless and faceless to men on the Ziggurat. They had nothing to say because nobody cared what they thought, and they knew it. They were the janitors, the meter readers, the lonely monks and the warehouse book keepers. The Untouchables.

The other category was the Loners. The Lepers were off the Ziggurat because they couldn’t get on it. Loners could find their place on the Ziggurat (maybe even at the top) if they wanted to; but they didn’t want to. They didn’t want to play all the political games that were necessary just to be a cog in a machine. They didn’t need the Ziggurat…sometimes were oblivious to it. They could sometimes pull in the highest salaries and Top-Tier women all while ignoring the hierarchy and its rules (which infuriated the Big Dogs). They were the explorers, inventors, Army scouts, buffalo hunters, mountain men, pilots, wildcatters, and pioneers in every field. Real-life examples might include Charles Lindbergh, Kit Carson, Nikola Tesla and the Wright Brothers. Tarzan, Conan, Batman and Zorro were a few fictional examples.

I hung on Uncle Si’s every word and thought about these lessons constantly.

***

I think Uncle Si must have known the bond I had to Mami, because every weekend we would warp-jump back to the Orange Grove. I missed her during the week, but this regular visitation provided the stability I needed.

My irritation at his unfaithfulness to Mami notwithstanding, I looked forward to any time I got to spend with Uncle Si. Unlike any other adult I’d known, he sometimes listened to me and considered my thoughts seriously. He taught me constantly on multiple subjects, but often asked me questions and seemed genuinely interested in finding out what my answer would be. I didn’t always have an answer, but it was really cool that he listened if I did.

Gradually, from remarks that came out in passing now and then, I was able to piece together some of his story. Uncle Si had been in some secret military unit when The Great Reset came about. (As near as I could figure, “The Reset” was an absorbtion of the USA into a foreign empire some time in the future…the future relative to my original time-space coordinates.) A veteran with an impressive record, he was drafted into the TPF and helped build the unit that would become the Erasers. He hadn’t known, at first, that the Erasers were to be a time-traveling death squad. After being ordered to lead a number of erasure missions, however, he secretly made a decision to desert and disappear. Although he’d never been a scientist, everyone had underestimated his technical aptitude. The way he told the story, he surprised even himself by successfully reverse-engineering a warp generator.

One part of Uncle Si’s personality that I didn’t understand or care for was his drinking. I hadn’t noticed him drink all that much before, but BH Station was evidently where he spent a lot of his time, and when he wasn’t busy doing something else, he indulged an addiction to straight vodka.

UPDATE: This book is published! Click here to buy on Amazon.

Click here to buy anywhere else.