As usual, rather than addressing Hallie Biden’s revelation, the Thought Police simply censored it. See, that’s what you do when you’re certain people would agree with you after hearing both sides.

Daily Archives: August 12, 2023

Paradox Chapter 13: How to Make Money With a Time Machine

There were many times when I would ask a question, that Uncle Si would use as an opportunity to teach me something, rather than just answer directly. There are few better examples than when I asked him how he became so rich.

He stopped what he was doing right then, and ushered me into a computer lab. Sitting down facing the monitor, he said, “Knowledge is power. You can turn that knowledge…that power…into money, then use your knowledge to make it grow.”

The computers resembled the ones I’d seen in computer stores, and in the office at school, but they seemed to be much faster, and capable of a lot more. Physically, the most noticeable difference was the monitors. The pictures on the screen seemed sharper, but also, the screens were flat and the entire monitor was only about the size of a laptop.

He brought up an image of a $100 bill on the screen. Not that I’d seen any $100 bills in real life before, but it looked very odd to me. On closer scrutiny, I noticed a printing date from 1880 and the unfamiliar phrase, “This note is legal tender for 100 dollars,” and “United States will pay to bearer 100 dollars.”

I knew absolutely nothing about money, but something struck me as paradoxical about this.

Before I could ponder it much, Uncle Si continued his impromptu lesson.

“Now, one way to get your initial stake is to jump a warp back to whenever, hire yourself out for an odd job…it was a lot easier to do in years gone by…and simply earn some cash. But I’m gonna help you get started quicker.”

He used a keyboard and mouse to choose a few options, then selected “print.”

One printer in a row of several came to life. After a few minutes, it shoved out a green rectangle. He grabbed it, rubbed it between thumb and forefinger, wadded it into a ball, straightened it back out, and handed it to me. I took it and, upon feeling it, immediately noticed the counterfeit bill had not been printed on normal paper. It was special, sturdy paper that felt like the real thing. He let me keep it, then printed some more bills.

He led me to a large chamber he called “the wardrobe.” I would have called it “the costume shop.” He picked out some clothes, disappeared into a dressing room, and emerged dressed like a wealthy cowboy. His sunglasses were gone—replaced by old-fashioned round spectacles. It was harder finding duds for me. Everything he had was too big for me, but with some alterations by a skilled seamstress he paged over the intercom, who used a very modern, computer-controlled sewing machine, I soon had a pair of farmer’s bib overalls, and a simple cotton shirt to wear. Uncle Si plucked a straw hat off a rack and dropped it on my head.

We took an elevator up into a hangar that I hadn’t seen inside before. We climbed into a fancy horse-drawn coach…only there were no horses. I inquired about this and Uncle Si simply replied that we could always acquire horses where we were going, if we needed them.

We took seats. He opened a hidden panel in the silk-covered inner wall of the coach, adjusting controls. Soon I felt the overwhelming sensations that told me we were shooting a warp.

***

When we climbed out of the coach it was night time. Our coach was parked near a horse livery in a city with no electricity and a whole lot of all-wooden buildings.

“Still got the C-notes?” he asked, walking toward a dark alley.

By the way he rubbed his thumb and forefinger together again, I inferred he was speaking about the counterfeit $100 bills. “Yeah. Are we in 1880?”

He shook his head. “New Orleans, September Six, 1892. Keep your eyes open and your mouth shut. I’m your father. We’re visiting from Texas.”

The dark alley fed out into a dirt street illuminated by lanterns on poles. It was quite a scene. Other pedestrians were out, and the way they were dressed made me stare.

Uncle Si checked an old-fashioned pocket watch ever so often, when nobody else was nearby. On one such occasion, I noticed a glow coming from the watch. Next time he checked it, I maneuvered around behind him to get a look. On the face of the watch was an LED display with a time readout and a digital map.

He found a small office annexed onto a wooden warehouse building, and ducked inside. We took our hats off inside the door, because according to him it was impolite to keep them on indoors in this culture. A fat bald man with jewelry on his hands asked what our business was.

Uncle Si waved his hat toward me and, in a western drawl, said, “Junior here just come into an inheritance. Dang fool kid wants to bet it on Corbett for tomorrow. I wasn’t gonna allow it, but I reckon it might teach him a lesson he’ll never forget.”

“On Corbett?” the fat man asked, as if not sure he’d heard correctly. “How much?”

Uncle Si gestured that I should hand him a phony hundred. I did.

The fat man took it from me, examined it and whistled. “That’s an expensive lesson.”

“Do it,” Uncle Si insisted. “If’n he learns it now, he’ll be less likely to make bigger fool mistakes once he owns the ranch.”

The fat man shrugged and happily pocketed the money. “Well, you are gettin’ four-to-one. Should Corbett win, you stand to make a tidy sum.”

Uncle Si and the fat man burst out laughing in unison.

Still snickering, the fat man handed me a newspaper. “Read the sports page, boy. Next time, at least get informed before your money burns a hole through your pocket.”

We visited several different bookies that night, Uncle Si performing variations on this same skit. We also collected more publications—newspapers, “hand bills,” and a black-and-white magazine with crude illustrations sprinkled through the text with a title on the cover that said: “Police Gazette.”

We checked into a hotel and Uncle Si told me, “Well, you got plenty to read tonight. I’ll be back.”

So I read the small stack of literature we had gathered.

There was to be a “boxing match” tomorrow—a heavyweight championship under “Queensbury Rules.” Only after finishing a few different publications did I figure out that meant boxing gloves would be worn. Evidently “bare-knuckle” boxing was a thing.

The champion was a man called “The Boston Strong Boy.” John L. Sullivan was his name, and he was really something. He had fought both with gloves and bare-knuckle. He had knocked out 500 men, and sometimes toured the country offering huge (for the time) cash prizes to anyone who could last four rounds with him. But few men even lasted one round with this savage bull of a man. He himself had never been beaten. He was strong, and tough, but he also must have had incredible endurance: one fight lasted 39 rounds, and in his most recent match, he knocked his opponent out in the 75th round!

Just from what I’d learned about fighting so far…including what boxing I’d seen on TV…I knew that you had to be incredibly tough, with tremendous stamina just to last 12 rounds, wearing 12-16 ounce gloves.

In the fight tomorrow, the gloves would be five ounces.

There were descriptions of the horrific damage inflicted on Sullivan’s victims throughout his career: broken jaws; broken ribs; opponents knocked through the ropes; intervention by the police to keep him from killing other men inside the ring.

Sullivan’s challenger was a bank clerk who went by the name of “Gentleman Jim” Corbett. He was outweighed by 25 pounds, and wasn’t nearly as strong as the Boston Strong Boy. Experts predicted he would be knocked out by the third round—though some imagined it was possible he might last into the seventh.

I didn’t understand what lesson I was supposed to be learning from this. I would never have bet on this fight if I hadn’t been told to. I was naturally tight with money anyway, never having much of it available at any given time. At least this was just counterfeit cash.

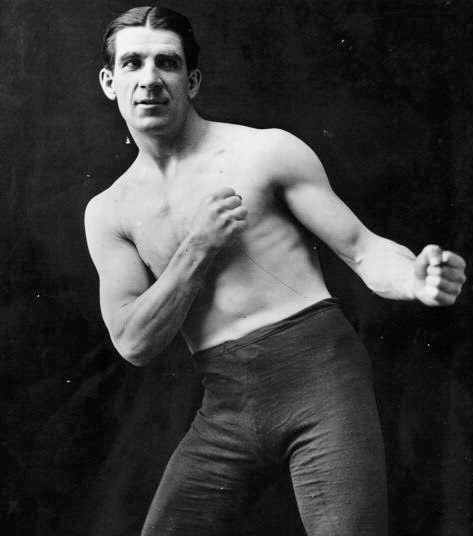

There were pictures of Sullivan in the magazine, and he did kind of look intimidating—though from the written accounts I half-expected him to stand eight feet tall and be built like the Incredible Hulk. He wasn’t nearly as tall or muscular as Uncle Si, but he had a big handlebar mustache and looked mean. His pose confused me though. His stance wasn’t very good, and his guard was horrible. It looked like both his arms were cocked to throw uppercuts. He looked wide open—like he was so tough that he didn’t care if you could hit him.

Uncle Si returned, nursing a bottle of vodka, and sat down on his bed, facing me. “Did you read about John L. Sullivan?” he asked. His speech was a little more forceful than normal; and his complexion kind of ruddy. This was normal when he drank.

I nodded.

“What do you think?”

“He sounds invincible,” I said. “I don’t think this Corbett guy stands a chance. Did you really intend for me to blow all those hundreds on bets for him?”

Ignoring my question, he took another swig from the bottle. “Remember. Remember everything you know right now. Okay?”

***

The next day we walked through the city to a place called The Olympic Club—an impressive arena with a boxing ring set up in the middle of acres of folding chairs inside a slapdash “auditorium” with no floor. There were thousands and thousands of men there, gathered around. I marveled at how heavily they dressed in such humid heat: nearly all of them were in suits, with long-sleeve shirts and vests under their jackets. And they all came inside wearing hats—some were top hats; some looked like the kind that restaurant in Los Angeles must have been modeled after (Uncle Si said they were called “bowlers” in Britain but “derbies” in America). Somehow Uncle Si had reserved ringside seats for us.

My eyes stung from all the tobacco smoke, and breathing was a struggle. Men pressed in around us from every side, and I was jostled probably three times every second for a while. An announcer finally stepped into the ring and began to project his voice into the multitude, hyping the coming fight and encouraging spectators to sit down so those behind them could see. When he mentioned “timed rounds of exactly three minutes—” I turned to Uncle Si. “Does he think we’re ignorant?”

My uncle shook his head, taking a swig from a metal hip flask, just as many other men were doing—mostly those who weren’t smoking pipes or cigars. “The sport of boxing hasn’t settled on universal rules. In most bouts up until now, a round lasted until somebody got knocked down, however long that took. Three-minute rounds is a new concept here.”

“Jeez,” I said.

“Yeah. Sullivan suffered so much damage in his last title defense, he decided he would only fight according to Queensbury Rules thereafter. Set a historic precedent, unbeknownst to him. Boxing is the way we know it because of Sullivan, when you think about it.”

I pondered how one person’s personal decision, made for whatever reason, could affect millions of people for centuries to come.

A man with a mustache just like the one Sullivan had in the picture was standing next to us. He narrowed his eyes while staring at us—perhaps because we spoke of the future as if we knew it, and the present as if it had already happened. Uncle Si ignored him.

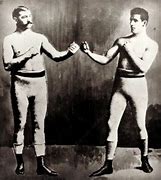

The boxers were introduced and stepped through the ropes along with their “seconds”—their corner men. Both competitors wore tight pants with leather boots, but were bare from the waist up. Corbett was lean, like he’d faithfully stuck to his roadwork for years. I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw “The Boston Strong Boy.” He didn’t resemble an athlete of any type—much less a legendary heavyweight champion.

“That’s Sullivan?” I blurted. “What a slob! He looks like 300 pounds of chewed bubblegum!”

It couldn’t be him. This flabby butterball was clean-shaven, and didn’t even resemble the Sullivan in the picture I’d seen.

Handlebar Mustache, next to us, flashed me a dirty look.

Uncle Si said, “Well, first of all, he’s over the hill. You can counteract Father Time if you’re fanatic about your conditioning. But he hasn’t been training; hasn’t defended his title in four years. He’s a hard-drinking over-eater who indulges himself too much—especially for somebody who has to fight a younger, faster opponent.”

I couldn’t shake the hype from all the sports writers. “But Corbett is a bank clerk who can’t take a punch!”

“Corbett is one of the very first ‘scientific’ boxers,” Uncle Si said. “He’s a pioneer of what Muhammed Ali will one day call ‘the sweet science.’ He’s got a trainer who fought the champ before; he trains with discipline; and studies his opponents before he fights them.”

The announcer finally finished bellowing to the crowd, then had his rules talk with the two boxers.

The bell rang.

Their stances weren’t much better than the awkward pose I’d seen in the Police Gazette. Sullivan kept his right cocked, but his left extended almost straight down to his left thigh, while he stalked the smaller man flat-footed. Corbett actually moved pretty well, but he had no guard whatsoever—both hands hung down around his waist.

And speaking of hands, I was dumbfounded by the gloves worn. Five ounce gloves looked like little more than mittens—not much of an improvement over bare knuckles, I would guess.

Sullivan charged like a drunken bull. Though Corbett was obviously agile, for some reason he allowed the ponderous old champion to back him into a corner. Uncle Si leaned forward with interest, as did most of the men around us.

With malice in his eyes, Sullivan wound up and threw a haymaker. He caught nothing but air. Corbett escaped while the blow was just building up steam. The smaller, quicker boxer grinned as he danced away. Before the round was over, Corbett backed into a different corner. Again, Sullivan loaded up for a big shot. Again his wild roundhouse missed as the grinning Corbett danced away untouched.

Corbett hadn’t even thrown a punch. He seemed interested only in making Sullivan look stupid. The crowd began to boo.

By the end of the second round Sullivan had yet to land a punch, and Corbett still hadn’t thrown one. However, Corbett had backed into all four corners. He ducked, dodged and danced out of harm’s way before Sullivan could tag him.

Uncle Si tapped my chest with the back of his hand. “You see that?”

“What?” I asked.

“Every time Sullivan loads up to swing that right…as if he’s not telegraphing bad enough already…he slaps his thigh with his left hand.”

“What’s that about? I asked.

“Not sure.”

Sure enough: next time Sullivan wound up for a haymaker, he slapped his thigh when he threw it.

“See it that time?”

I nodded.

“Never, ever a good idea to be so predictable. I’d be real surprised if Corbett hasn’t noticed it.”

The crowd was turning ugly fast—booing and jeering. At first I assumed this was due to the champion’s unprepared condition and dismal performance. But their contempt was aimed at Gentleman Jim for running away. At one point, Corbett turned away from Sullivan, faced an ocean of his hecklers and waved both hands at them. “Wait a while,” he said with a grin, “you’ll see a fight!”

It occurred to me that neither man had a mouthpiece. They must not have been invented yet.

In Round Three, Corbett backed into a corner yet again. Sullivan looked determined not to let his quarry escape this time, and actually refrained from slapping his thigh before launching that freight train of a right roundhouse. But before he could get off, Corbett suddenly came to life. He stepped into a left hand that landed flush in Sullivan’s face, and followed up with a flurry that got the champion moving backwards for the first time.

Corbett peppered him with shots from both hands, and before I knew it, Sullivan was the one trapped in a corner.

Uncle Si laughed out loud and drank from his flask. Bedlam broke out in the audience. The din of yelling voices was deafening. Men waved their hats, or stripped off jackets and swung them in circles by the sleeves. Judging by all the hanging jaws, this turn of events was a shock to most.

When the bell rang, blood was gushing from Sullivan’s nose.

“Corbett’s ready to go to work, now,” Uncle Si said. “He still might play with his food a bit, but he’s measured his man and he’s ready to start building the coffin.”

Handlebar Mustache glared at my uncle, who just tossed back a pull from the flask.

At the start of round four, an infuriated Sullivan charged out in pursuit of Corbett again, hell-bent on avenging his broken nose. But the elusive boxer sidestepped and danced out of harm’s way time and again. I was sure I could feel Sullivan’s frustration.

The fight progressed according to a pattern of Sullivan charging and Corbett retreating, but periodically surprising the champion with flurries and counterpunches.

“Wow—Corbett’s footwork is really good for his time,” Uncle Si observed. “He’s riding circles around John L with that bicycle.”

“I guess it should have been four-to-one for Corbett,” I admitted. “Everyone had it backwards: he’s the invincible one.”

“Don’t be stupid,” Uncle Si said, with a disdainful sneer. “Footwork is the foundation, but you can’t neglect the other stuff. Both these guys have terrible form. Granted: Corbett doesn’t have to fight a perfect or even textbook bout here. But still…look at those punches.”

I studied Corbett with a new focus for a bit. His guard was still completely down. When he did flick out punches, they were stiff-armed, windmill-style blows that an uncoordinated child would throw. The fact that they were bedeviling Sullivan made them no less ugly.

“You’re right,” I said.

He shrugged. “He doesn’t have to be great to be the better man today. But almost any contender from a more refined era would beat him. Jack Johnson would give him fits. Gene Tunney would take him apart. Even Max Baer would make him pay for his sloppiness.”

Evidently, Handlebar Mustache had heard enough.

He glared at Uncle Si, saying, “You must be a sports writer or somethin’. Is that what you are, cowboy?”

Uncle SI didn’t reply, but screwed the cap back on his flask and slipped it in his pocket.

“Just who do you think you are, anyway?” Handlebar Mustache demanded. “You must figure yourself a fight expert. But I’m gettin’ tired a’ hearin’ all this malarky from you and your hayseed boy.”

“At ease, shitbag,” my uncle said, simply, still watching the match.

“What’d you call me?” Handlebar Mustache obviously didn’t intend to wait for a verbal answer to his question. He lurched to his feet, tore off his hat, peeled out of his jacket and vest with angry, jerking movements.

I barely caught the movement of Uncle Si’s hands as he shot up from his chair. His left blurred up to land open-handed on the man’s face with a loud smack. It caught the guy on the mouth, and up into the bottom of the nose. Handlebar Mustache staggered back from the humiliating slap, then his head snapped back from the follow-up right that caught him on the jaw.

As Handlebar blinked and swayed, Uncle Si grabbed him by the shoulder, spun him around and tripped him forward to fall on his hands and knees.

The men surrounding us had diverted their attention from the bout to watch this much more decisive action. Handlebar pushed himself up off the ground, retrieved his vest, dug through the pockets, then came at Uncle Si with a knife. I was transfixed by the economy of movement that followed. Uncle Si slapped the man’s knife hand from the outside, pushing it onto a trajectory which would widely miss the target. Shuffling forward a step, his hand now gripping Handlebar’s wrist, Uncle Si yanked hard on the captive arm while pivoting his upper body, driving his elbow into the man’s temple with all the torque of his shoulders behind the blow. In the same motion of the natural recoil of a delivered strike, Uncle Si grabbed a fist full of hair, pulling the man’s battered head forward and down, as he sprang into the air and drove his knee up to meet the man’s face.

Handlebar fell backwards and lay still with his eyes rolled up in his head, blood leaking from his lips and nose. It didn’t look like he’d be pulling himself to his feet any time soon.

Uncle Si produced his flask again, took a drink, and with a wicked smile asked, “Anybody else want to stick his nose in my business?”

There were no challenges from the onlookers. A couple of them lifted Handlebar off the floor and carried him away through the crowd.

Uncle Si glanced at me. “I’d advise against using a knife in close combat. But if, for some reason, you ever have to use one in self-defense, don’t lead with it.”

He went back to watching the match. Eventually, so did I.

It seemed to me that Corbett’s style was more about timing than technique. He kept one step ahead of the champion, but timed his movements to evade attacks when Sullivan made a sudden rush to close the distance. Nearly every offensive effort from Sullivan instigated a combination of punches from Corbett to the head and body. Corbett’s punches still looked sloppy, but they landed with a high degree of accuracy.

“See the way he’s working the body?” Uncle Si asked me, after Corbett had thrown a double hook to the ribs.

I nodded.

“That can take the wind out of even a fighter who’s in shape. You’re gonna see Sullivan slow way down if this keeps up.”

It did keep up, and Sullivan slowed down.

My mood changed from one of astonishment that the immortal, invincible John L. Sullivan could be so badly outfought, to a sickening sadness at how he was being systematically dismantled. A large portion of the crowd, however, had a markedly different reaction. Their enthusiasm for destruction never waned—they simply switched loyalty from Sullivan to Corbett. Passion, when coupled with a fickle nature, is frightening.

By the 14th round, Corbett was landing almost at will, and Sullivan’s offensive efforts were getting fewer and farther between.

“Corbett’s just playing with him, now,” Uncle Si remarked.

“Seems to me Corbett could finish him now,” I said.

“But he’s smart, and being methodical. Sullivan’s still got a puncher’s chance, even though his best chance evaporated after the first couple rounds were done. You never want to get careless, especially with a dangerous puncher. Corbett’s gonna wear him down with attrition until there’s no risk.”

The match wasn’t even competitive. After that, I lost any hope that it might be.

During Round 20, Uncle Si looked a little disgusted as he said, “Corbett needs to quit playing around and put him out of his misery. This is just embarrassing.”

Sullivan’s face was covered with angry welts. There were red marks all over his torso as well. He wasn’t even throwing punches anymore. As he gasped for breath, his primary concern seemed to be simply remaining on his feet.

“Remember this,” Uncle Si said. “There’s a lot of principles at work here that have application outside of this match. Sullivan’s not used to being on defense…so he’s got no defense. He doesn’t know how to fight going backwards, and he’s got no choice but to go backwards now. He’s hurt, and completely out of gas, too. He’s helpless.”

“Why doesn’t he throw in the towel?” I asked.

“Pride.”

The crowd, now tired of the matador-and-exhausted-bull show, was hissing and jeering again.

***

In Round 21, Corbett must have decided it was now safe to let it all hang out. He landed a left hook to the head with an audible smack that reverberated through the noisy, smoke-filled building. The champion staggered backwards, and Corbett pursued, stinging him with jabs and crosses as if his fists were a swarm of bees.

Sullivan backed up to the ropes and reached out clumsily, groping for the top one to use as an anchor and keep his feet. As he tried, and failed, to grab the rope, Corbett loaded up for the coup de grace. Why not? There was no danger anymore.

Corbett caught him right on the button with a freight-train of a right hand…one of those Hollywood haymakers you’d never get away with on a target that wasn’t already out on his feet.

Sullivan’s knees buckled. He toppled over and hit the canvas with a thud, then rolled over on his back. The place went crazy. Everyone was on their feet, yelling.

I couldn’t hear what Uncle Si told me, but judging by the movement of his mouth I think it was, “We’ve seen enough. Let’s go collect your money.”

UPDATE: This book is published! Click here to buy on Amazon.

Click here to buy anywhere else.