You’d have to be blind to not notice how stupid-happy I was after that short little evening and morning. Still, Dad didn’t press me on it. He left me alone with my thoughts and fresh memories for the next leg of our trip.

I did finally ask him if it would be possible to correspond with Gloria. He turned thoughtful, gave me a long look, turned back to the road, thought some more, and finally said, “It’ll be tricky, but maybe we can work something out.”

***

After a few more days, I was able to function again and actually think about something other than Gloria Benake.

While meandering through the plains and deserts of the Southwest in that hot rod Willys, we got into a discussion about time travel. Dad asked me a question he had to rephrase a few times. But once I understood what he was getting at, I would think about it a lot as I got older.

“Okay, Sprout: You’ve been to a few different points in time already. You started out with your life there in St. Louis. Then you jumped back to the Orange Grove. You jumped forward with me to BH Station. Then way back to New Orleans for Sullivan-Corbett. And now back to this road trip. Did I get it in the right sequence?”

“Um, yeah.”

“Really? You’re sure?”

“Yeah.”

“How do you figure? How can you be sure of any linear sequence when the illusion of time is no longer relevant?”

My reply was steeped in wisdom and just slopping over with all the intellectual prowess of a pre-adolescent boy: “Huh?”

“The only solid evidence we have that time even exists is entropy,” he said. “But anyway, of all the space-time coordinates you’ve visited, New Orleans is the earliest. BH Station is the latest. So wouldn’t the correct sequence of your travels begin with New Orleans, and end with BH Station? And where we are right now should be in the middle, right?”

“No,” I said, vigorously shaking my head.

“Why not? That’s proper chronological order.”

“Because that’s not the order of how it happened.”

“So you’re saying that St. Louis is the singular reference point; that everything else is lined up in the sequence according to that coordinate.”

“Um, yeah,” I said. “I guess so.”

“But why? How do you know what sequence is correct? 1892 came before any of the other coordinates, right?”

“Well, yeah, but…”

“And 1934 comes after 1892. Then 1947 comes after 1934. So the chronologically correct sequence is New Orleans, the Orange Grove, then this vacation, St. Louis, then BH Station. That’s just simple math. 1892 is the earliest date, so of course you went there first. 1934 is the next earliest date. So that’s where you went next.”

“That may be the historical sequence,” I said, “but I visited those times in a different sequence.”

“How do you know?”

“Because I remember how it happened.”

“Ahh. So your memory is calibrated from that one reference point, back in St. Louis. And your memory records remain consistent throughout the series of warp jumps. Why is that?”

“Because that’s just the way it happened.”

“What you’re saying is, that’s how all the puzzle pieces fit together in what you consider reality,” he said. “But can we even define reality anymore? Is our concept of reality even relevant?”

“I don’t understand what you’re asking,” I said.

“I’ll answer the question for you: Yes. You’re right. And the supporting evidence is relative growth. Even though you’ve been moving backwards and forwards through time, you’re still aging—according to a sequence that is anchored in the reality you lived in St. Louis. You didn’t grow decades older when we went to BH Station, and obviously you didn’t grow younger for every year we went back, or you would have ceased to exist before we got to these coordinates. So you’re right. But why are you right?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“I don’t know either, Sprout. But I’ll tell you—I sometimes wonder if that truth is ironclad. Maybe reality can change—and our memory will self-adjust to accept it. Wouldn’t that be a mind-blower?”

I didn’t answer. This whole conversation sounded crazy.

“Pretty smart scientists have proposed that time itself is just a stubbornly persistent illusion,” he said. “Other scientists have determined that there are at least six dimensions beyond the four that we perceive. Now, somebody with a warp generator can pierce the illusion and jump through unperceivable dimensions. That means it’s theoretically possible to exist outside of time altogether.”

I wasn’t following his logic, so I remained quiet.

“Let’s say it’s Thanksgiving and the Macy’s Parade is underway. You’re watching it from the top of a skyscraper, with binoculars, while most people are watching it at street level. Down there, the Budweiser float has just passed the people standing at Times Square or wherever. Right in front of them is the Coca-Cola float, and if they lean to peak around that Coca-Cola float, they’ll see the one with the Charlie Brown and Snoopy balloons.”

“Okay,” I said, trying to picture the scene he described.

“So you remember the Budweiser float. You see the Coca-Cola float in front of you right now, clear as day. And you think you can see far enough to predict that the Peanuts float is coming next. Budweiser is the past, Coca-Cola is the present, and Peanuts is the future. Well, up on top of the skyscraper, you see all three floats simultaneously. You can see every float in the entire parade. You don’t have to remember or predict anything, because past, present and future are all there for you to clearly see. In fact, there is no past or future. Everything is present.”

“How does that relate?” I asked. “You say I’m on the skyscraper…outside of time. How could I actually get there? Who could actually be there?”

“Outstanding question, Sprout. Maybe you can’t ever get there. Probably only God is outside time like that, looking into our stream and seeing everything at once. But if He’s there, looking at past, present and future simultaneously…then that’s the reality that supersedes all others, ain’t it?”

I had no answer for that; nor was I prepared for what came next.

“So if that’s the true reality, then there is no actual separation. There is no linear progression. It’s just a stubbornly persistent illusion—it’s an imposed limitation. Well, I suspect our subconscious mind can glimpse into the unperceived dimensions sometimes. Some people more than others, probably. But that might explain where some of our weird dreams come from. Or bizarre phenomena like deja vu.”

“Dreams?” I asked.

“I have dreams, sometimes, that don’t make much sense,” Dad said. “But when I analyze them, I wonder if they’re not evidence that my subconscious is perceiving into different streams. If there is one true reality, then not only do past, present and future exist simultaneously in a given stream; but even the different streams themselves…the different realities…are all actually one. God simply determines which illusion we are limited to and calibrates our memory accordingly. You, me, anybody with a warp generator can trespass into illusions we weren’t assigned to, but our calibration anchors our cognition to the reality we originated in—at least during conscious thought. And our biology, too.”

“I’m confused,” I admitted. “I don’t understand what you’re trying to say.”

He chuckled and shrugged. “Well, at least remember this conversation. Think about it. One day you’ll understand at least what I’m asking. And if you ever think you’ve found an answer…let me know.”

“Okay.”

Not long after that, we were driving somewhere north of Roswell, New Mexico, and I experienced an oppressive, creepy, foreboding sensation. I got goose bumps, and began looking around in and outside the car, wondering if the source of the feeling was visible.

Dad noticed me looking around and studied me. He noticed the hair on my arms standing up, and pulled the car over onto the shoulder of the road. That’s when I noticed that he had goose bumps, too.

“What is it?” I asked.

“You tell me,” he said.

“I don’t understand.”

He rubbed his own arm, then looked down at mine. “You feel that, right?”

“I feel…something,” I said.

He got out of the car, gesturing for me to do the same. “Describe what you feel,.” he said.

I did my best to put the sensation into words.

He nodded, using his more expansive vocabulary to clarify my attempt at description. “Ominous. Tumultuous.”

“Maybe evil…?” I suggested.

“Interesting,” he mused, looking out over the plains. “I guess this might make sense.”

“It does?” I asked. “What does?”

“Maybe it wasn’t a weather balloon after all,” he muttered.

“Say what?”

“I guess you never read the details about this,” he said, then pointed out into the plains. “Somewhere out there is a ranch—not very far, I’d guess. Right about here and now, something has crashed, is crashing, or will crash very soon at that ranch. You never heard of the Roswell UFO?”

“I’ve heard of it,” I said. “Area 51. Hangar 18. Right?”

“I dunno,” he said. “I’m not a UFO nut. But now I know something is happening here, too.”

“Here, too? You lost me, Dad.”

He chewed on his lip for a while, studying first me, then the landscape. “Tell you what: let’s take another field trip real quick.”

We got back in the car, took off, and immediately warp-jumped to a place he called “S.A. Station.” The scenery was exotic and beautiful.

It turns out “S.A.” stood for South Africa, and the year was 1958. But we had only stopped there to pick up the VTOL with cloaking capability.

The VTOL (Vertical Take-Off and Landing) was quite an aircraft, even without the Predator technology. It had retractable, forward-swept wings and cowled propellors that could swing from vertical to horizontal. But Dad distracted me from examining it much by showing me some equipment similar to what the Erasers used.

It was like a heavy poncho—the outside of it covered with thousands of little L.E.D. screens. Wires crisscrossed inside the fabric of the poncho. For every screen, there was a microcamera on the opposite side of the poncho, recording whatever it “saw.” So the LED screens displayed live footage from behind whatever or whoever the poncho covered. No matter what angle you looked at it from, you simply saw a distorted image of the background on the far side of it. An electronic, active camouflage. Dad said that more advanced cloaking tech had come out since the poncho was made, available in jumpsuits and facemasks. He said the suits were very heavy and hot to wear, and they still just distorted the light rather than truly enabling invisibility; but made a person or vehicle extremely difficult to detect, unless you knew where and what to look for. He turned it on, and it became just a visual anomaly. Then he handed me his sunglasses and told me to put them on. When I did, I could see the poncho, with all its tiny LED segments glowing.

“That’s why you wear these all the time,” I said. “What are they?”

He hung up the poncho, shut it off, and took the shades back. “Relatively simple technology. The lenses block ultraviolet light, and are also polarized. The polarization keeps the LEDs from tricking you.”

“So you can see the Erasers, plain as day,” I said.

He nodded. “One of my science labs is working on a contact lens prototype. For now, we’ve got these.”

“Can I get a pair?”

“I guess so, Sprout. But let’s hope you never need them.”

We strapped into the VTOL and took off—up and away. We shot a warp and Dad cloaked the craft as we approached a large city.

There was a park or something with a little patch of woods inside the city. Dad guided the VTOL down through a gap in the trees and landed it expertly. We disembarked. Using the electronic compass in his “pocketwatch,” Dad navigated on foot to the edge of the copse, coming to a halt before breaking through the treeline. He held his arm out sideways to keep me from emerging into the open.

The city we saw from our ground-level perspective was quite an eyeful. Tall columns lined the streets, colorful banners hanging from them. Heroic sculptures were placed all over. The architecture of the buildings was alien to me. Some of it could perhaps be described as art-deco, but most of it looked like something else—gleaming new, but stylistically a throwback to antiquity.

Upon a large parade ground were perfectly- arranged mass formations of soldiers and vehicles. Just beyond this, dominating the scene, was a colossal structure, shaped like a sporting arena. The enormous stadium reminded me of pictures I’d seen of the ancient coliseum in Rome, only much bigger. A roar of a great multitude cheering rose out of the stadium.

“You’ve been studying history, right?” Dad asked in a hushed tone. “You know where we are?”

“Nazi Germany,” I said, noting the hundreds of huge red banners with black swastikas inside white circles.

“Specifically, the Olympiad,” he said. “Berlin, 1936. The Olympic Games. I discovered this at a Nuremburg Rally, but it’s here, too.”

“What’s here? I asked.

“The Big Spooky. Relax for a minute. What do you feel?”

Before I could answer, what looked like clouds of swirling confetti wafted up from the stadium and into the sky—defying gravity. The roar of 100,000 voices shook the air again.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Pidgeons. Or doves. Some kind of birds. Supposed to symbolize world peace or something.”

“Yeah, right,” I said with a sneer, remembering what the Nazis actually brought to the world.

“Concentrate, Sprout. Evaluate what you feel.”

I tried to both relax and concentrate at the same time, ignoring my conditioned response to all the swastikas, and the inherent danger of the situation which caused us to speak quietly, lest we be discovered.

“It’s a lot like what I felt back in Roswell,” I said, incredulous that the same unusual oppressive atmosphere would be here on the other side of the planet and 11 years earlier. “Only, there’s also…”

Dad nodded. “Right. In this case, it’s ominous…but it’s also got a seductive quality, doesn’t it?”

“Seductive?” I repeated, confused. “You mean like in sex?”

“That’s not how I mean it. I mean appealing. There’s almost a temptation to want to be a part of the great, momentous event going on.”

“Yes!” I agreed, amazed at how accurate his description was of something I personally felt. “That’s it, exactly.”

He nodded again. “It was the same at the beginning of the Bolshevik Revolution. But I’m not taking you there. This is a big enough risk.”

“But this is a sporting event,” I observed. “Not a UFO landing.”

“Right. I don’t know exactly how the Olympiad is so significant in the scheme of things, but there’s no denying the sensation. And that extra, seductive aspect…it must be the added zeitgeist factor—like at Nuremburg and 1917 Petrograd, and 1959 Cuba, and…”

“What’s a zeitgeist?” I asked.

“It means ‘spirit of the times.’ It’s when mass portions of a population all get on the same page. They all jump on the same bandwagon, share the same emotion collectively, believe in the same ideology, adopt the same goals…this is one coordinate right here and now that has it in droves.”

“Too bad we can’t watch the Games,” I said.

“Yeah. Jesse Owens won four gold medals for America and embarrassed Der Fuehrer right out of the stadium. But we’re taking a big enough risk already, Sprout. Neither of us speak the language and you don’t want to go barging into one of these socialist Utopias without your papers in order. Besides, the games last for two weeks, and the cloaking tech is gonna drag down our batteries much sooner.”

He took one last glance toward the imposing stadium, and sighed. “What’s really going on here, under the surface? It’s more than pole-vaulting and discus throws.”

We returned to the VTOL and lifted off out of the little copse, into the sky.

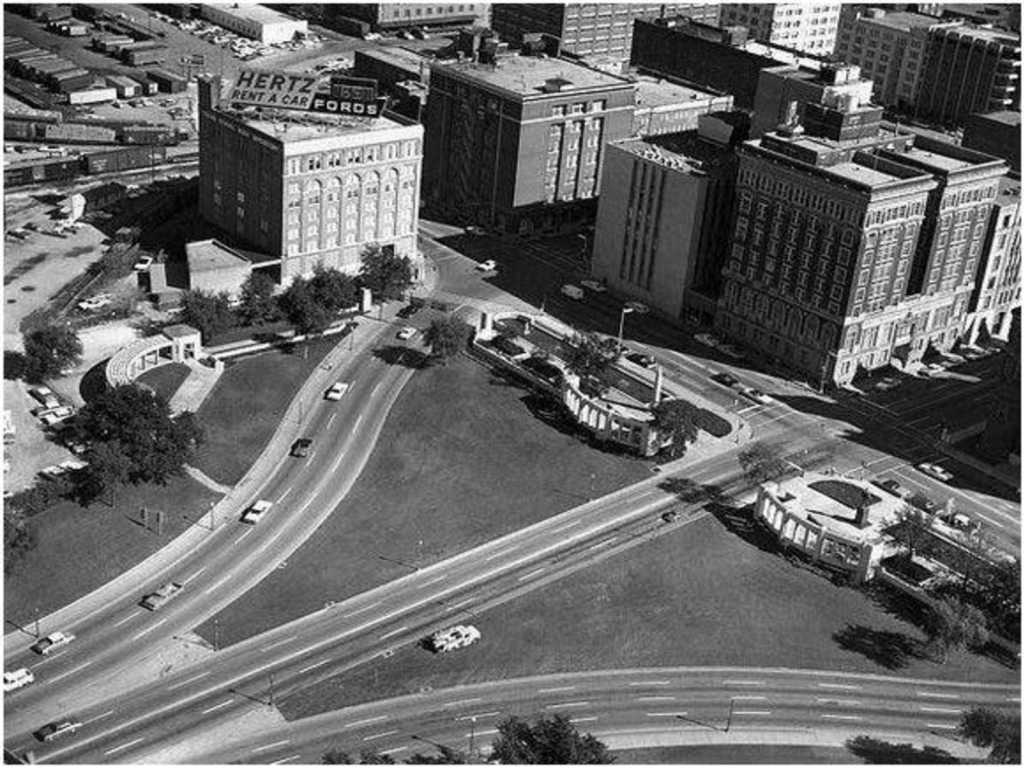

We jumped a warp once airborne, and Dad began to breathe a bit easier. But soon we were approaching another city—more modern, but at least as big. He noticed my curious expression, and announced, “Dallas, Texas. November 1963.”

We approached a downtown area, descending on the way. “This…sensation you felt,” he told me, “I discovered it by accident, but I started tracking it through history. It happens a lot, at coordinates all over the four-dimensional map. We’re just hitting some of the highlights this time. For some reason, in the ’60s they spring up all over, like popcorn. Like weeds. Most of them are like the Olympiad—meaning I don’t know exactly what’s so significant about the coordinate. I picked this one for this trip because it’s fairly easy to grasp the significance.”

He lowered the VTOL to a landing in a grassy field in the middle of a square bordered by multi-story buildings, and shut it down while leaving the cloak active.

“This is such a public place, out in the open,” I observed, as we stepped outside. “What if somebody bumps into the VTOL?”

Dad shrugged. “People are gonna see all kinds of stuff here tomorrow that doesn’t make much sense. Whatever doesn’t fit The Narrative will be ignored or discredited. At worst, somebody’s story of an invisible futuristic craft parked in Dealey Plaza the day before the assassination will be easily dismissed as just another ‘crazy conspiracy theory’.”

“Assassination?” I asked.

He just nodded.

We strolled around the plaza. Dad studied the top of a few buildings; a rain gutter and a grassy area behind it; sections of the street; trees, light poles and signs. “You feel it?” he asked me.

I nodded. The ominous sensation was as thick as gravy. You couldn’t see it, hear it, smell it or touch it, but it was there in abundant quantity. I wondered if being exposed to deadly atomic radiation was like this, or if you wouldn’t even know you were exposed to it until your skin started falling off. Or maybe some people could feel it—as I was feeling whatever this was, now.

Assassination. Dallas. 1963. Dealey Plaza. These words came together in my mind and triggered something in my long-term memory. “Kennedy! JFK—this is where he was shot?”

“Not ‘was’ shot. Will be shot. Tomorrow.”

It began to rain. Pedestrians around the plaza opened umbrellas. Dad ushered me back to the VTOL.

Before he took off, he opened a metal case and activated a squadron of microdrones, disguised as flying insects. One at a time he remote-piloted them to different spots around the area, landed them, and placed them on “stand-by.”

“You’re going to record the assassination?” I asked, strapping in.

“Yup,” he replied. “I plan on getting a lot of footage from multiple angles and vantage points. Nobody here and now knows about my drones, and therefore they can’t be tampered with.”

He fired up the engines and we took off.

“Why?” I asked, remembering his speech about how changing history would split the timestream and tip off the CPB to our presence.

Dad shrugged. “‘Cause I want to know what really happened. Don’t you?”

I didn’t answer. The JFK assassination happened long before I was born, and hadn’t particularly interested me so far. The name “Lee Harvey Oswald” echoed through my mind. They knew who the killer was, so there was no mystery to solve. To me the battles of the Crusades or the best Rose Bowl games ever played were much more interesting.

***

Our next stop was Chicago in 1968 during the Democratic National Convention. Yup—same old goose bumps. Same ominous, foreboding sensation. The “Big Spooky” was on the scene. We mixed with the crowd a little bit, seeing what we could see. I watched smelly, long-haired potheads and drug addicts clash with police in riot gear. Dad seemed more interested in listening to people not engaged in violence—whether they were in a conversation or shouting slogans to any who might hear.

“What’s different about this coordinate?” Dad asked me once we had broken away from the crowds and had some relative privacy.

“Nobody was fighting at the other coordinates,” I said. “There was unity. Right?”

“Yes and no. There may not have been a manifestation of violence in Berlin or Dallas, but there was violence in the air. And don’t let the conflict here fool you—there’s still a zeitgeist at work…a powerful one. This is just a struggle for control of the left-wing. People on both ‘sides’ want the same thing; it’s just that the New Left want it faster than the Old Left, while the Old Left wants to maintain the facade of actually loving what they’re trying to destroy.”

“Who wins?” I asked.

He shrugged. “Hegel.”

“I don’t know who that is, Dad.”

“You’ll learn about him when you’re older.” He pointed to the building where the convention was being held. “Thesis.” Then he pointed to the rioting protestors. “Antithesis.” Now he waved toward me, then himself. “The world we grew up in is the synthesis.”

I had no interest in politics yet, and let the subject drop.

“The ’60s is the beginning of the end for America; but it still has a lot going for it if you can ignore that,” he opined, as we strolled back toward where he had hidden the VTOL. “Fantastic decade for a young man—especially the last half.” He craned his neck to ogle some women in miniskirts walking toward the convention. “It’s easy to get girls; females are still feminine; and obesity is still fairly rare.”

Meeting Gloria had jump-started a process in my body and mind that would soon result in radical changes. My attitude toward the opposite sex began to change with it, so I did take an interest in Dad’s observation.

***

Our next stop was another November—this one in 1910 at Brunswick, Georgia. After leaving the VTOL cloaked in an area surrounded by tall trees, Dad and I snuck over to a small, lonely, terminating rail station. We chose a discreet point to observe from, and ate snacks quietly while a train rolled up in the dark of night.

It was the shortest train I’d ever seen, and I whispered as much to Dad.

“That’s a private car in between the locomotive and caboose,” he whispered back. “Came all the way from New Jersey. If you knew anything about railroads, you’d know somebody powerful had to pull some strings to get this little train’s routing priority above all the crucial freight and passenger trains. In these times, the railroads are the national infrastructure. They’re how people get mail, food, fuel…everything. You don’t make room for some private ‘duck hunting trip’ in the middle of all that unless you’ve got enormous clout.”

“Duck hunting trip?” I echoed.

Dad nodded toward the private rail car. It looked fancy. The windows glowed dull yellow—probably from kerosene lamps inside. Shadows flashed in the flickering light, betraying movement inside.

“That’s their cover story,” Dad said. “Do you feel anything?”

I shook my head. “Feels normal.”

He nodded, then gestured for me to follow. We left our observation post and crept quietly toward the train. When we came within a few yards of the private rail car, the Big Spooky hit me with such force, I nearly wet my pants.

Dad looked at me, an expectant question in his eyes. I nodded.

On the other side of the train from us, the conductor opened a door on the rail car, and a handful of men began filing out. I could make out feet and legs by peering underneath the train. I heard their voices, too.

Now the Big Spooky throbbed so excessively that my eyes watered.

Dad grasped me by the shoulder and steered me back toward our surreptitious vantage point. As we went, the oppressive sensation faded. Once back in our spot, I felt tremendous relief.

“Why didn’t I feel anything until we got close?” I asked.

“It’s concentrated, here,” Dad explained. “I’m not saying we can’t find the Big Spooky at earlier dates, because we definitely can. I have. But here and now it’s like…I don’t know…a seed, or something. Maybe a beach head. From here it grows and spreads out—like to the other places we found it.”

“It sure was intense right there,” I said. “Is this another one you don’t understand, or is there something significant about these coordinates?”

“Oh, it’s significant,” he said, solemnly. “The men getting off that train—they’re gonna climb on a boat that takes them to a private venue on an island, where they’ll have a meeting. In that meeting, they’re gonna develop a plan to destroy the United States of America, and freedom…and a whole lot of other stuff.”

“Destroy America?” I asked, confused. “But…”

“Not tomorrow,” he said. “Not next week. Not by some sudden catastrophe. In fact, their plan won’t seem to have made much of a difference for a long time. For three years there won’t be any evidence at all that an American could point to. But they’ve put something in motion. Three years from now, they’ll take a big step toward their goal.”

“Their goal…” I mused. “Destruction of the USA?”

He nodded. “In seven years they’ll take another step. They’ll suffer a few setbacks here and there, but 19 years from now they’ll take another big step. In 22 years they’ll start taking huge steps, one right after the other…starting in another November, in fact.”

I didn’t understand what he was alluding to, but I was getting the idea that November was a popular month for the Big Spooky.

“There will be plausible deniability for generations,” Dad went on. “In the post-war USA, it’s the most prosperous time anyone in world history has seen. Only a crackpot would argue that anything could be wrong, right? Even back in the coordinates you came from, almost nobody could see the problem.” Now he pointed to the locomotive. “America was a big, powerful, fast-moving engine, with a lot of momentum built up. It took over a hundred years for the cancer, eating away at her from the inside, to be obvious to enough Americans to even be mentioned in the mainstream. By the time there’s enough people aware of the problem to demand repairs, the poison will have spread everywhere. It’ll be too late. The locomotive will come off the rails; the boiler will explode; the whole thing will collapse into a pile of mangled metal. Then all the foreign vultures we’ve helped and protected over the generations will move in and pick through the scrap, taking whatever’s valuable to them. That was happening in the coordinates I came from.”

His speech had lost me. He must have realized my confusion, because he sighed and forced a grin as he tousled my hair. “But you and me have a way to cheat Fate. At least we can survive the slow-motion train wreck. And some day you’ll take an interest in history. We’ll talk then—a lot. Then all this should make more sense.”

We made our way back to the VTOL. Once inside it, I asked him, “Is there something special about us? I mean, why can we feel the Big Spooky but nobody back in Dallas or Berlin did?” I frowned and scratched my head. “Or did they? That would be even more confusing.”

Now Dad’s smile didn’t appear forced. “That’s a great question, Sprout.” He leaned back in the pilot seat and folded his hands. “You ever hear the parable of the frog?”

I shook my head.

“If you want to boil a frog,” he said, “you don’t throw it into a pot of water that’s already hot—it’ll jump out. What you do is put it in the water with the temperature nice and comfortable…then gradually turn up the heat in stages. Be patient. The frog gets used to water that’s 70 degrees, then you turn it up to 80. It’s uncomfortable for the frog at first. It may complain a little, but if you’re patient, it’ll become acclimatized to the discomfort. Then you can turn it up to 90. It’s uncomfortable, but not uncomfortable enough for the frog to jump out of the pot. The Founding Fathers said something, in the Declaration of Independence, along the lines of: ‘men prefer to just suffer, while evils are sufferable.’ That’s what the frog does. If you keep cranking up the heat, but you do it gradually enough for each new level of misery to become the status quo for a while, eventually you’ll boil the frog alive.”

“Have you ever done that to a frog?” I asked, disgusted.

He sneered. “Of course not. I’m not a sick, sadistic dirtbag. This is a parable. A metaphor. It’s how America will be destroyed. It’s why the people who wouldn’t take shit from the Japs, or the British, or the Barbary pirates, will let their freedom and future be stolen from them by enemies in their own government. In fact, they’ll obediently fund the thieves who do it. But I think it might also be why people living in certain coordinates never notice the Big Spooky. It comes on them gradually enough, they acclimatize to it. You and I notice it because we ran into it from ‘normal’ times, and it hit us all of the sudden. Like a stinky house—if you live in it, you get used to the smell, and don’t notice it. But if you enter from out in the fresh air, it hits you hard.”

“I guess that makes sense,” I said. “But what is the Big Spooky? What causes it?”

“I don’t know yet,” he said. “I wish I did.”

***

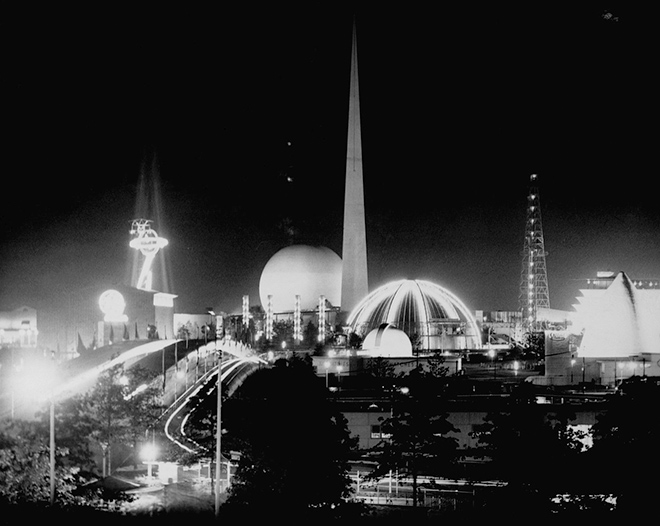

We jumped a warp and came down inside another city—this one easily the biggest I’d ever seen. It had art-deco skyscrapers to prove it. We landed inside a vast expo complex and, this time, Dad turned off the cloak and shut all the power down. I asked him about this as he locked the VTOL’s hatch. He told me people would assume our craft was an exhibit and, by the time organizers looked into it, we would be gone.

It was 1939 in New York City and the goose bumps sprang up from that oppressive, ominous sensation. Again, Dad said there was no obvious reason why the Big Spooky was present at that space-time coordinate, but it was unmistakable—although at a weaker dose than other stops on our tour.

He also revealed the purpose of this tour: to confirm that I recognized the same sensation at the coordinates where/when he experienced it.

The research portion of our experimental time tour over, he advised me to try ignoring the Big Spooky and enjoy the rest of the day.

Over the course of the day I gradually grew accustomed to the Big Spooky—kind of like how I hardly noticed the noise of traffic, barking dogs and gunshots around the old trailer park. I did enjoy the 1939 New York World’s Fair, very much. We spent the entire day there exploring “The World of Tomorrow.” I was fascinated by everything—in detail and as a whole. And I could tell Dad enjoyed it all, too.

There was a big robot (named “Electro the Moto-Man”); a time capsule; a carnival-style ride that took us through a “city of the future”; some fantastic, futuristic (in an art-deco way) locomotives and trains, showed off in a special railroad park; new fabrics and inventions on display (including the “tele-vision” and a “View-Master” which you could use to look at three-dimensional slides); new music, sculptures, paintings and other art; and a science fiction convention.

Evidently this was the first world sci-fi convention ever held. Dad bought me an armload of books (and some of the very first superhero comic books, about characters like the Human Torch and the Submariner) while he stopped and chatted with some of the authors.

Of course most of the speculative “technology of tomorrow” envisioned at the World’s Fair was long obsolete by the time I would be born, but I still found it incredibly cool. I had never owned or seen a View-Master before, so the 3D slides were new to me. It was neat seeing what television was like when the technology was new. And it was cool discovering what artists, authors and scientists thought the future…my lifetime, give or take…would look like, even though they were almost all completely wrong.

For most of my life after that initial exposure to the 1939 World’s Fair, I found myself wishing that the future some of those dreamers imagined had turned out to be the real one.

UPDATE: This book is published! Click here to buy on Amazon.

Click here to buy anywhere else.