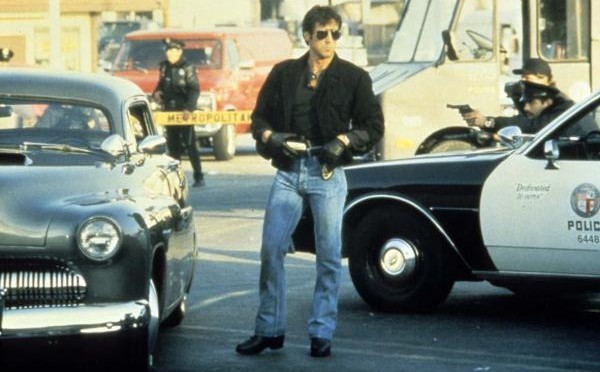

I mentioned this chase scene recently in my post about Cobra. Despite swinging ’60s soundtrack and the advance of both special effects and automotive technology since this cop flick was made, this is still the best car chase I’ve ever seen. So help me, if somebody so much as mentions any of the abysmal Fast and the Furious movies in this context…well, just count yourself lucky that you’re not within slapping range.

Here’s some rumors and trivia I’ve picked up here and there about this famous scene:

- The old fart with glasses at the wheel of the Charger is a stunt man who did the actual driving for the shoot.

- Steve McQueen did some of the stunt driving as well. Those little throttle blips just before the upshift were him showing off.

- At first the suspension of both cars were tuned to handle quite well (especially considering the era and the skinny bias ply tires), but the director wanted them to skid around the corners more dramatically and so had them de-tuned again.

- That 440 Mopar was bone stock, as was the Dodge body/frame.

- The Mustang’s 390 was warmed over a little, and the chassis stiffened to handle those spine-kinking jumps.

BTW younger generation: This is what an actual Dodge Charger looks like. Those pregnant 4-door luxury sedans on the streets now? They are a result of some German engineers having a few kegs too many at Oktoberfest and mixing the ugliest body styles from both Daimler-Benz and Chrysler (and it should have been called a Coronet or something, though even the Coronets were never that ugly). Putting a badge on it that says “Charger” is just sick German humor.

Geez, a whole lot of Pontiacs get in the way of this epic vehicular battle.

I’ve heard people say that the movie Ronin has a great chase scene. I just watched it again, and it’s a decent flick with some good driving scenes. The chases aren’t as good as this one, though I think I know why some people find it exciting. I just blogged about it last time.

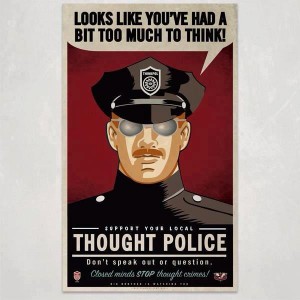

orst. It’s intentionally insulting, first of all–no doubt a ploy to get an emotional rise out of me (all the more reason for me to not take the bait, I suppose, but c’est le guerre). And it’s also intentionally misleading, by somebody who evidently didn’t read the book. It’s got all the fingerprints of an SJW troll attempting to protect unwashed brains around the world from a counter-narrative.

orst. It’s intentionally insulting, first of all–no doubt a ploy to get an emotional rise out of me (all the more reason for me to not take the bait, I suppose, but c’est le guerre). And it’s also intentionally misleading, by somebody who evidently didn’t read the book. It’s got all the fingerprints of an SJW troll attempting to protect unwashed brains around the world from a counter-narrative.