Here are some titles I picked up for 99 cents apiece from the Big Based Book Sale:

Rebel Heart (Engines of Liberty Book 1)

By: Graham Bradley

For centuries the British Empire has ruled territories the world over, maintaining its grasp on its far-flung colonies by way of magic and brute force. Any successful attempt at rebellion is short-lived, as the rebels do not have the benefit of wizardy on their side.

For centuries the British Empire has ruled territories the world over, maintaining its grasp on its far-flung colonies by way of magic and brute force. Any successful attempt at rebellion is short-lived, as the rebels do not have the benefit of wizardy on their side.

The most recent attempt at secession happened in the New World in 1776, some two hundred years ago. General George Washington nearly succeeded at rallying his countrymen in a military revolt against the Crown. But disunity and infighting ultimately brought them down, and Washington was executed in a public spectacle.

Most people gave up. But not all.

The cleverest and most driven survivors went to ground. They learned from their mistakes. They planned, they plotted, they tinkered and they toiled. They began to develop new weapons and machines that would level the playing field. With technology at their fingertips, anyone could stand toe-to-toe with a British mage and come off conqueror.

The uprising has been a long time coming. The arsenal is as large as it’s going to get. Now all the “technomancer” army needs is soldiers, young patriots like Calvin Adler, who has had enough of the mages pushing him around.

Freedom beckons, if he will but pay the price in blood, sweat, and tears.

This is the New Revolution.

BRUTAL: A Sword & Sorcery Fantasy (THE BRUTAL SWORD SAGA Book 1)

By: James Alderdice

He has no name. His past is a mystery. His future is etched in blood…

The Sellsword knows an opportunity when he sees one. When he rides into the border city of Aldreth, he can tell that th e power struggle between two feuding wizards needs a solitary spark to ignite into all-out-war. As he sets the corrupt paladins and demonic adepts against each other, he’s not surprised when the blood begins to flow…

e power struggle between two feuding wizards needs a solitary spark to ignite into all-out-war. As he sets the corrupt paladins and demonic adepts against each other, he’s not surprised when the blood begins to flow…

But after the alluring duchess catches his eye, the Sellsword puts himself in harm’s way to protect her and the innocent people of Aldreth. To save the noble few, spells and blades won’t stop the Sellsword from leaving a swath of righteous carnage in his wake…

Brutal is an action-packed grimdark fantasy in the vein of classic pulp fiction and Sergio Leone spaghetti westerns. If you like gory battles, larger-than-life characters, and witty humor, then you’ll love James Alderdice’s gritty tale.

Talk to a Real, Live Girl: And Other Stories

By: Paul Clayton

2021 !WINNER! in Science Fiction — Los Angeles Book Festival! Readers’ Favorite 5 Star review: Talk to a Real, Live Girl And Other Stories by Paul Clayton is a short collection of light sci-fi tales. The flagship story is Talk to a Real, Live Girl. Disillusioned with the extreme societal and political changes on Earth and a ruined relationship, Alex leaves home to work at a mine on Kratos, a distant planet. Kratos also offers some free time diversions, one being particularly appealing to men far from home; robot females who are perfect and always willing. Alex has no real interest in them, despite his loneliness. Then, one day he meets Traci, a “real, live” girl. Do Alex and Traci have any real hope of a future together? In the next story, The Lawn, Bob Hanlon struggles mightily to come to terms with his forced retirement and the strange presence that seems to have taken up residence in his overgrown yard. In the third story, Happy Acres, a couple finds their new life on Mars less perfect than what they had been promised. Finally, the first two chapters of a novel-in-progress about the fabled Lost Colony of Roanoke complete this collection of stories. In Talk to a Real, Live Girl And Other Stories by Paul Clayton, readers find entertaining stories that almost read like episodes of beloved classic sci-fi TV series. The main story, a poignant tale of loss, new possibilities, and adventure, makes some subtle, near humorous observations about contemporary American society and what the future could hold. The other two stories, while lighter fare and shorter, are no less interesting. These stories are a quick, enjoyable read, and Paul Clayton has a talent for immersing readers almost immediately in their narrative, including the bonus chapters at the end. Any message the author is trying to convey does not get in the way of the basic flow of the stories, which is a desirable feature. He also draws attention to other stories he has written, and readers will find themselves willing to invest time in reading these. Alex has fled a broken marriage and a society on Earth grown hostile toward men. Landing on the mining planet, Kratos, known to its male work force as “Boyz Wurld,” he hopes to lose himself in hard work, drinking, and the illusion of female companionship provided by robots. Will that be enough? In time, Alex finds himself longing to Talk to a Real, Live Girl. Predictably, there aren’t many on Kratos. Then he finds Traci, as well as the dream of a new beginning back on Earth—a normal life—if only the forces controlling Kratos will permit it.A genuine love story, Talk to a Real, Live Girl explores consequences of a #MeToo movement run amok, and of adaptations brave individuals may be forced to make.

2021 !WINNER! in Science Fiction — Los Angeles Book Festival! Readers’ Favorite 5 Star review: Talk to a Real, Live Girl And Other Stories by Paul Clayton is a short collection of light sci-fi tales. The flagship story is Talk to a Real, Live Girl. Disillusioned with the extreme societal and political changes on Earth and a ruined relationship, Alex leaves home to work at a mine on Kratos, a distant planet. Kratos also offers some free time diversions, one being particularly appealing to men far from home; robot females who are perfect and always willing. Alex has no real interest in them, despite his loneliness. Then, one day he meets Traci, a “real, live” girl. Do Alex and Traci have any real hope of a future together? In the next story, The Lawn, Bob Hanlon struggles mightily to come to terms with his forced retirement and the strange presence that seems to have taken up residence in his overgrown yard. In the third story, Happy Acres, a couple finds their new life on Mars less perfect than what they had been promised. Finally, the first two chapters of a novel-in-progress about the fabled Lost Colony of Roanoke complete this collection of stories. In Talk to a Real, Live Girl And Other Stories by Paul Clayton, readers find entertaining stories that almost read like episodes of beloved classic sci-fi TV series. The main story, a poignant tale of loss, new possibilities, and adventure, makes some subtle, near humorous observations about contemporary American society and what the future could hold. The other two stories, while lighter fare and shorter, are no less interesting. These stories are a quick, enjoyable read, and Paul Clayton has a talent for immersing readers almost immediately in their narrative, including the bonus chapters at the end. Any message the author is trying to convey does not get in the way of the basic flow of the stories, which is a desirable feature. He also draws attention to other stories he has written, and readers will find themselves willing to invest time in reading these. Alex has fled a broken marriage and a society on Earth grown hostile toward men. Landing on the mining planet, Kratos, known to its male work force as “Boyz Wurld,” he hopes to lose himself in hard work, drinking, and the illusion of female companionship provided by robots. Will that be enough? In time, Alex finds himself longing to Talk to a Real, Live Girl. Predictably, there aren’t many on Kratos. Then he finds Traci, as well as the dream of a new beginning back on Earth—a normal life—if only the forces controlling Kratos will permit it.A genuine love story, Talk to a Real, Live Girl explores consequences of a #MeToo movement run amok, and of adaptations brave individuals may be forced to make.

Scout’s Honor: A Sword & Planet Adventure (Scout series Book 1)

By: Henry Vogel, Bruce Bethke

After crash landing on a long-lost colony world, Terran Scout David Rice’s life got really tough. Thrown from the space age to the steam age in the blink of an eye, David is drawn into a desperate battle to save the beautiful Princess Callan from treacherous air pirates and ruthless slavers. Trapped in a world of clashing swords, brutal savages, royal machinations, and desperate rescues, David’s greatest battle is against his growing feelings for the betrothed Princess. With her life and the fate of two kingdoms hanging in the balance, which will David choose: love or honor? Told in a relentlessly fast-paced style, Scout’s Honor is an exciting homage to the classic tales of Edgar Rice Burroughs and Leigh Brackett, as well as the cliffhanger-driven energy of the early science fiction movie serials. If you long for honorable heroes and feisty heroines, treacherous villains and loyal companions, get Scout’s Honor and join David’s journey!

After crash landing on a long-lost colony world, Terran Scout David Rice’s life got really tough. Thrown from the space age to the steam age in the blink of an eye, David is drawn into a desperate battle to save the beautiful Princess Callan from treacherous air pirates and ruthless slavers. Trapped in a world of clashing swords, brutal savages, royal machinations, and desperate rescues, David’s greatest battle is against his growing feelings for the betrothed Princess. With her life and the fate of two kingdoms hanging in the balance, which will David choose: love or honor? Told in a relentlessly fast-paced style, Scout’s Honor is an exciting homage to the classic tales of Edgar Rice Burroughs and Leigh Brackett, as well as the cliffhanger-driven energy of the early science fiction movie serials. If you long for honorable heroes and feisty heroines, treacherous villains and loyal companions, get Scout’s Honor and join David’s journey!

Yeah, I’m in a sci-fi & fantasy mood lately. I also picked up a few classics for free, at the Big Based Book Sale.

There is an alternative to the Marxist garbage being rammed down your throat on all the mainstream/legacy platforms. Support what you love, or it goes away.

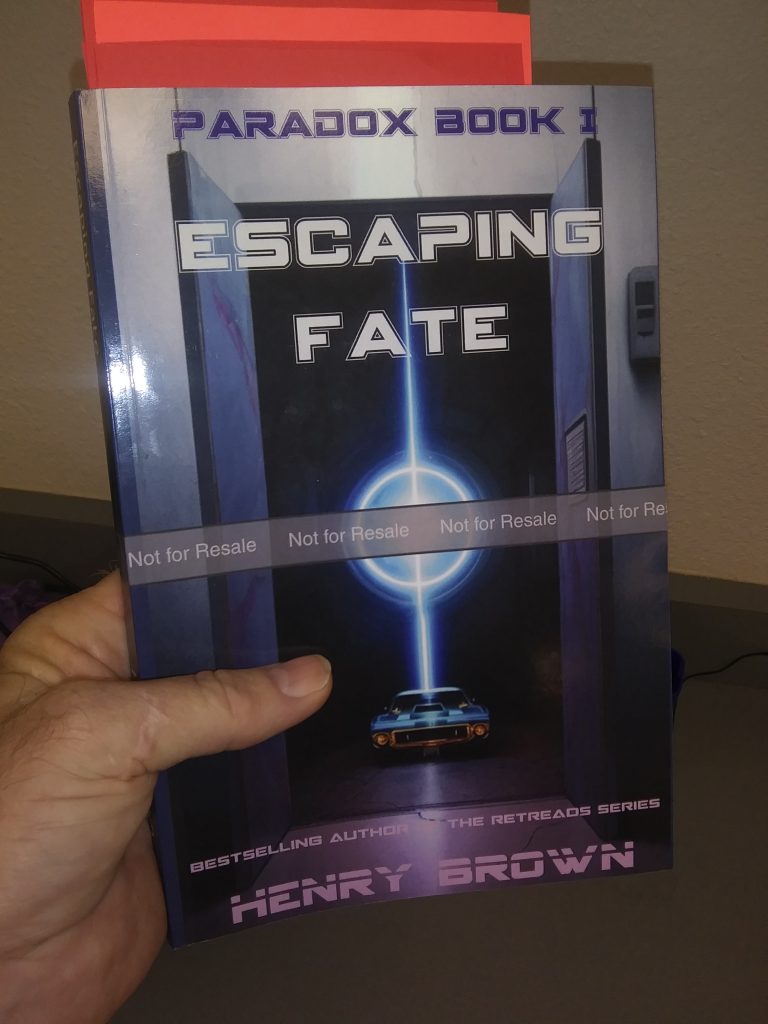

Pete Bedauern began his life as a latchkey kid in a run-down trailer park with a single mom, living on stale hot dog buns and bleak prospects. Those were the cards Fate had dealt him, and Pete was on his way to becoming an angry young man. Then Pete’s estranged uncle burst on the scene to punch Fate in the mouth.

Pete Bedauern began his life as a latchkey kid in a run-down trailer park with a single mom, living on stale hot dog buns and bleak prospects. Those were the cards Fate had dealt him, and Pete was on his way to becoming an angry young man. Then Pete’s estranged uncle burst on the scene to punch Fate in the mouth.