Nothing seemed unusual when I got back to the trailer after school. But it was a segue into something that would prove very unusual.

Mom was watching TV. She turned briefly to check who was walking through the front door, and said, “Hey. There’s some hot dogs in the fridge.”

“Okay,” I said, and stumbled over piles of laundry and empty cigarette cartons on the way to the fridge. I found the weenies and buns, and pulled them out. The buns were stale, but we had no other bread. I stuck one in the toaster but didn’t push the lever down just yet. I unloaded stacks of slimy dishes from the sink until I found a Teflon pot. I rinsed and wrung the dish rag several times before dripping some dish detergent on it. I rinsed out the pot, then scrubbed it with the rag without waiting for the water from the tap to warm up. Once reasonably clean and rinsed, I filled the pot with water, set it on the burner of the stove that still worked, and began hunting for a match.

“Hey Mom, can I borrow your lighter?” I finally asked.

“Bring me a wine cooler please,” she said, eyes still glued to the TV screen.

I reopened the fridge, plucked a pink bottled beverage out of a four-pack, and delivered it to her on the couch.

We lived in a three-bedroom trailer, so I had my own room—which was nice. The third bedroom was filled with Mom’s extra shoes, clothes, and other stuff, so effectively we had just two bedrooms. Only one toilet worked, but if one of Mom’s future boyfriends turned out to be a plumber, the second one might get fixed. The dingy carpet in our living room sagged down to form a depression where a section of the floor had rotted away under it, but Mom usually stacked something in that spot so it wasn’t so obvious.

I handed her the wine cooler and she dug around in her purse until she found the lighter, and handed it to me.

That purse was scary. There was so much junk in there, I sometimes imagined her hand coming out with a dead rat one of these times.

I lit the burner and the water slowly began to warm. I went down the hall to my bedroom to retrieve a paperback to read while I waited for the water to boil.

“Can you make me one, too, Sweetie?” Mom asked.

“Yeah,” I said, transporting another weenie from the refrigerator to the pot.

During a commercial break, she turned from the TV to address me with eye contact. “So. Something else about your Uncle Si, huh?”

“What?” I asked, realizing he must have paid her a visit or made contact with her somehow.

“Recovering from a coma,” she explained. “I figured he would die in that hospital, or hospice, or whatever it was. But he looks really healthy. It must not have been as serious as we heard.”

“You saw him today?” I asked.

She nodded. “He stopped by. He really does favor your father.” She twisted her lips, examining me. “And you. If your father wasn’t such a loser…well, anyway, Simon reminds me why I got with your dad in the first place.”

“Oh, puke, Mom,” I said.

“I know,” she said digging a cigarette out of that frightening purse. “But I sure didn’t feel like puking those first few weeks with him.” She snapped her fingers and did a little seated dance on the couch that she obviously found more cute than I did.

“What did you talk about?” I asked. “With Uncle Si?”

She shushed me, showing her index finger, as her head whipped back toward the television. Her show was on again.

I read the book until the weenies swelled, then pushed down the lever on the toaster.

“Why do you always have to toast the bread?” Mom asked, eyes still locked onto the idiot box. “You don’t use enough electricity already?”

“I don’t always toast it,” I protested. “Only when the bread’s stale. It kinda’ covers the bad taste.”

“Toast mine too, then. Let me see.”

I navigated the obstacle course between the stove and the couch, delivering our meal to eat together in front of the TV.

The phone rang. Mom’s show was back on, so she gestured toward the phone without looking away from the screen. “Get that, Sweetie? Mommy’s still eating.”

I was still eating, too, but I answered the phone.

“Who told you you could use the phone, loser?” demanded a haughty voice I had come to hate over the years.

“I’m not using it; I’m answering it, first of all,” I said. “And secondly…”

“Shut up, moron,” Allyson interrupted. “I need to talk to my mother.”

She consistently emphasized “my mother” when referring to Mom, as if Mom was her mother but not mine. I considered asking, “how’s it feel to need?” But that would prolong our conversation, which I really didn’t want to do; and Mom would take her side in the resulting argument, as always.

“She’s watching TV,” I said.

“Well no shit, dumbass,” Allyson retorted, in a tone that was almost gleeful. “Just because you can’t walk and chew gum doesn’t mean everybody else is stupid, too. I promise. Mom can hold the damn phone to her ear even while the TV is playing. Now give her the phone and go back to fingering your own asshole.”

I handed the phone to Mom. Even though her show was still on, Mom took it and, with a cheery tone of voice, said, “Hey girlfriend! How’s your love life?”

My hot dog bun was no longer warm enough to mask the stale taste. As I finished eating, Mom chatted and cackled. Her show ended, and I knew she couldn’t possibly have paid attention to it as well as to her daughter, but Mom wasn’t even slightly annoyed—quite the opposite.

I grabbed the paperback and retreated to my room.

Mom called me back to the living room, later, when both her TV show and the phone call were done.

There was another show on TV now, which Mom didn’t like as much.

“What do you think of Uncle Si’s offer to do some after-school work for him?” she asked, during the next commercial break.

“I’d really like to do it,” I said, already feeling defeated. I had already been allowed to have a dog, so my quota of favors had been used up for some time to come. There was no way she’d let me spend time with a cool guy related to my dad.

She surprised me by saying, “If you do it, you have to stick with it. You can’t start, then decide you’re bored with it after a few months.”

“Huh?” was all I could say.

She lowered her voice to a conspiratorial tone. “This could free me up to take that job at the jewelry store, for the closing shift. But you can’t tell anybody, or we might lose the food stamps and everything else.”

“You mean…I can do it?” I asked, incredulous.

“You’re sure you’ll stick with it?”

“Yes!”

“No going back, now,” she said, with an admonishing tone. “If I take this job, you have to keep yours. If you decide later you don’t like it, you have to keep doing it, anyway.”

I didn’t know why everybody was questioning my commitment that day. Maybe because my enthusiasm about the dog faded when she turned out to be a trouble-making retard. “It’s a deal,” I said.

It turns out, the owner of the jewelry store had just sweetened the job offer a few days before. It was hard to imagine how Uncle Si’s timing could have been any better.

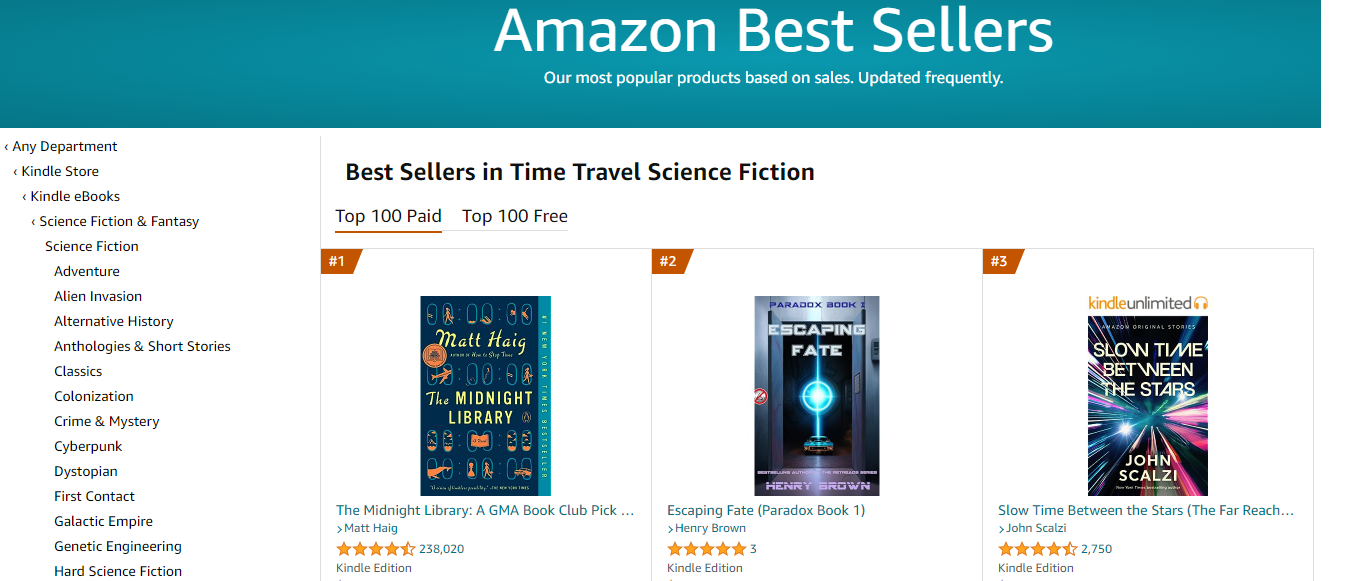

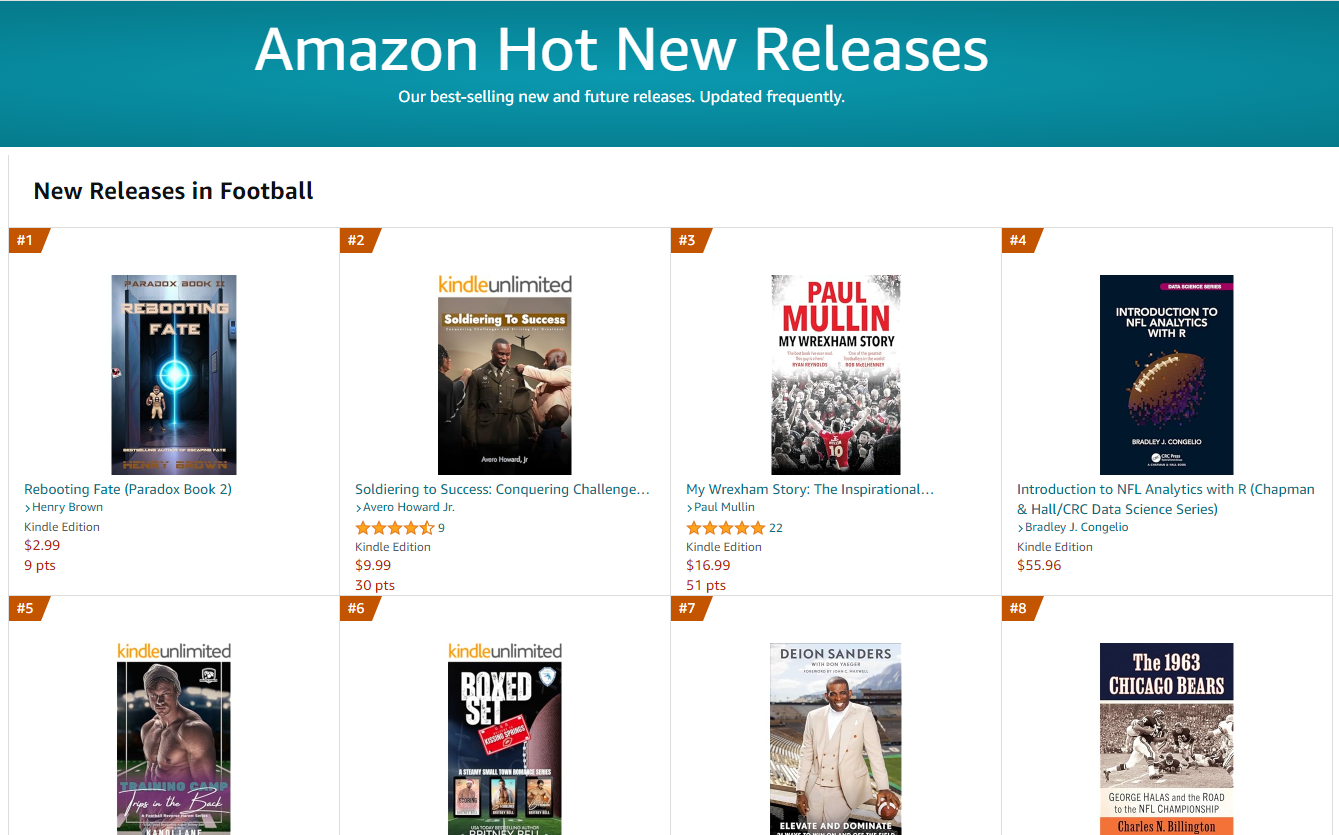

UPDATE: This book is published! Click here to buy on Amazon.

Click here to buy anywhere else.