Virtual Pulp is pleased to once again host THE INFAMOUS REVIEWER GIO as he interviews the author of the Islands of LOAR: Sundered.

Gio: Book 1 came out over a decade ago, what exactly drove you to write it and then have it published? Looking back now, would you make any changes or have done anything different?

Ernie Laurence: The Islands of Loar series is the last series I wrote. I have written over 40 novels-worth of stories, but never went through any editing or publishing. When I married back in 2005, my wife found out and encouraged me to publish. So, I began the long process of actually learning the craft. I took several classes, mostly technical writing classes, and learned about editing and eventually publishing. Since Loar was the last, I felt the most confident (and the least emotionally attached if I didn’t do well) publishing that series first. I referred to Sundered as “my Isaac”, a child to be sacrificed on the altar of public opinion, so to speak.

I had been telling stories for a long time and they were always well received. I am a forever GM when it comes to tabletop gaming and some of those elements have made it into my books, though I have expanded the stories well beyond that. When I started down the road to publishing and let people know, I received a lot of encouragement from those close to me. The initial versions were well received with some helpful criticism. Thean, for example, came across as kind of flat to a lot of people and several told me to tighten the story by dumping him. However, I knew he had a purpose and so I went back in and thickened his story a lot. I’m glad I did that.

The only difference I would make, and actually have made, is to bring the book more in-line with what I’m doing with the tabletop gaming system I’ve been working on for 7 years now. The other books grew more aligned with it as I began to develop it. A couple of years ago, I went back and made some tweaks so that would be the case for all of them. An example is that I changed Spenciel’s “class” from monk to kaisoma. And I’m really proud of that word. Heh.

Gio: The first thing that strikes me as I read Sundered is the introduction of a multitude of characters, and not just minor characters but major players. Was that a conscious decision, to add so many characters as the story unfolds?

Ernie Laurence: Yes. I read a lot. I’m somewhere over 4000 books now. And the ones that I really enjoyed were those with a rich cast – the Wheel of Time for instance. In fact, I wrote the Islands of Loar right after Crossroads of Twilight published in January of 2003. I read an article at one point that said, “write each character as if they were the main character” and it used Han Solo as the example. Han wasn’t just the shuttle pilot for Luke, Ben, and the droids. He had his own backstory, motivations, goals, and rich personality.

So every character in Loar is like that. Even the minor ones have their own story. As I have time, I fill in those tidbits on my wiki for readers to get more depth as they like.

Loar is a story about people in desperate straits. The only way they are going to survive is together. I needed a large cast to emphasize this point. It wouldn’t just be one hero with extraordinary powers in just the right circumstances. It would be an entire world of people working together to save themselves from annihilation. Sundered sets that stage by showing the people as disconnected from each other as the Islands are from the original planet they used to be a part of.

Gio: Without giving out any spoilers, what is the ‘Sundering’ and what caused it? I ask because for example in Lord of The Rings we know at all times what the cause of all the troubles in Middle Earth is, but in Loar it seems like this is not as clear (at least not in book 1).

Ernie Laurence: The Sundering is the explosion of the planet. Some force, or maybe several working in conjunction, literally tears the planet apart. It is only through the elemental magic of the sorcerers that anyone survived at all. The geomancers hold the twenty largest chunks where people have gathered together. The aeromancers held the atmosphere over them. The pyromancers channeled the heat of the explosion around the chunks, and the hydromancers used the specific heat capacity of the ocean to absorb what the pyromancers couldn’t redirect. Once the cataclysm itself ended, they then worked together to stabilize their world. I intend on writing more about all this and perhaps even turning the part immediately post-Sundering into a MMORPG where environmental changes the players make working together can become permanent. It will be a much more cooperative MMORPG than standard titles.

I don’t want to specify what caused the Sundering here because that’s part of what the characters (and readers) have to find out as they move through the series. There are a lot of hypotheses and the characters of the world think they know early on. It isn’t revealed until later if they are right, partially right, mostly wrong, or if the Council of Wind is just making things up to control people.

Gio: There are a lot of politics involved in Book 1. This makes Sundered much more complex than your typical action/fantasy novel because we have individuals in power who basically play this game of chess with people’s lives. Politics and legislature seems to play a big role in this world. Was that also a conscious decision to go that route, and where did you get this idea of writing these pretty intense political debates from?

Ernie Laurence: A large part of the hook of the story is for the reader to figure out who the bad guys really are. The politics are an integral part of the story because it sets the saviors of the world up as the initial antagonists. They are a council of monarchs, tyrants with near absolute power who control the atmosphere around the Islands. If you do not obey, they simply remove the air from around you and you die. They can do this for their entire Island so there is no opportunity for rebellion. This is in large part because the geomancers and pyromancers are gone. The hydromancers, for whatever reason, have been relegated to river rats scraping a living out of meager fares carting people around on boats.

This intense political atmosphere drives against the work of the protagonists for a large part of the story as things get worse and worse through the series. Ultimately, I set up a counter-plot to it, but that’s not in Sundered so I’ll say no more. The politics and economics, though, are reflective of that overarching thought: Loar won’t survive if they are divided and the political actions of the aeromancers are dividing the people more and more. Sadly, most of them are just too tired, too downtrodden by living on a broken world to fight back. They need some jolt to wake them from their stupor, some shining light to guide them out of the darkness. There’s even a chapter called “Boiling the Batrachos” (Chapter 39) where the Dhorens are introduced. Its purpose is to show that the few people who are speaking out against the tyranny, the bards, are being systematically rounded up and silenced and no one is stepping up to defend them. Batrachos means “frog” so it’s a familiar analogy for most readers. The society has been on a slow-burn fall into tyranny and they are just accepting it so long as they have air and food.

There are certainly parallels with our own world, at least in the most general sense. I don’t have specific political groups or individual politicians in mind when I write the aeromancers. They are their own characters. But the idea of tyranny versus liberty and America’s slow slide into the former certainly has a strong influence on my thinking and how I crafted the political climate of Loar.

Gio: Going back to the multitude of characters we encounter, it seems like there is no one main character here, but readers might find a personal favorite character as they further explore this world. In your mind, who is truly the main character or protagonist here?

Ernie Laurence: One of the conscious decisions I made when starting out on this world was that this story was bigger than one person, one hero. The main protagonist is all the heroes working together and those who join them later (yes, the cast definitely grows). There are three “main” threads in Sundered, each with its own cast. Doogan’s group, Spenciel’s group, and Thean’s group. In Sundered, they begin to cross paths as I set up the main conflict over the four book arc. In book two, “The” protagonist, the group, starts coming together as choices and circumstances make that necessary. In terms such as you are asking about, it is more helpful to think of the protagonist as the group and the antagonist as a question mark.

Gio: we’re now on Book 4. What do you have in the works for the immediate future and what can we expect to see regarding Islands of Loar? Are you planning to focus more on the novels or tabletop games?

Ernie Laurence: I have a lot of pots on the stove, so to speak. My main project right now is to finish the art for the Player’s Handbook for the tabletop system. We already have an introductory module out for sale so it’s important to get the core rules out soon. Yet, as far as novels go, I am going to polish a novella I wrote called “Steel” for publishing. I’m also working on bringing my very first novel up to date maturity-wise, polish it and then publish. This is the first book I wrote that turned out to be more than 350,000 words. So it will be broken into a trilogy. Right now it’s just called “Demon War”, but that will be the trilogy(?) and each book in the series will get its own name.

Plans to revisit Loar in the future are laid out. There are unwritten novels from different time periods that I want to write. The arrival of humans pre-Sundering, the Godswar that leads up to the Sundering itself, something immediately following the Sundering (maybe a video game), the War of Wind and Fire, and then another related series that I don’t want to say anything about as of yet. There is a hint about it in Book 4 of this series that you are reading.

There are a lot of novels written already though that need polish and publishing so I will likely go back and forth between those and new works as well as continually writing modules and the other core rulebooks like the Creature Codex, the Game Master Guide, Manual of Mysticism, Economic Encyclopedia, and so on.

osted

osted

g John Lennon, and it got me to thinking (dangerous, I know). As an armchair historian and anthropologist, I’m fascinated with the radical change in our country between the end of WWII and the escalation of our involvement in Vietnam (roughly 1946-1966, let’s say). I don’t mean technology, though certainly that played a part. I mean culturally and ideologically there seemed to be a sort of paradigm shift in the mainstream—especially the younger demographics. Plenty of people can pontificate why it happened, including me, but you actually lived through it. I’d like to get your reflections on it. Did you notice it happening? What did you think of it at the time?

g John Lennon, and it got me to thinking (dangerous, I know). As an armchair historian and anthropologist, I’m fascinated with the radical change in our country between the end of WWII and the escalation of our involvement in Vietnam (roughly 1946-1966, let’s say). I don’t mean technology, though certainly that played a part. I mean culturally and ideologically there seemed to be a sort of paradigm shift in the mainstream—especially the younger demographics. Plenty of people can pontificate why it happened, including me, but you actually lived through it. I’d like to get your reflections on it. Did you notice it happening? What did you think of it at the time?

e (like yours) and writing some of my own. I still don’t want to swallow this pill, but it’s really looking like there’s no money to be made in old-school men’s fiction. There are few red-blooded American males left in our culture, it seems to me, and very few of them have an interest in reading. Some authors are making a go of it with niche sub-genres, but only those with the time and talent to build a platform of followers on the Internet.

e (like yours) and writing some of my own. I still don’t want to swallow this pill, but it’s really looking like there’s no money to be made in old-school men’s fiction. There are few red-blooded American males left in our culture, it seems to me, and very few of them have an interest in reading. Some authors are making a go of it with niche sub-genres, but only those with the time and talent to build a platform of followers on the Internet.

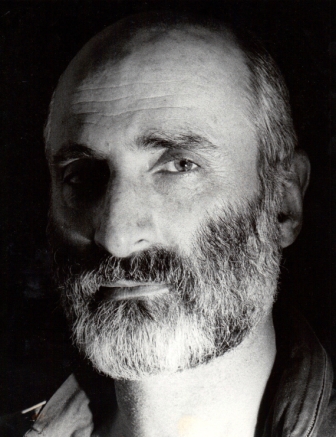

ture fiction, author Len Levinson.

ture fiction, author Len Levinson.

en a Sergeant in WWII and participated in the liberation of Paris. After I handed in the first SERGEANT, which was DEATH TRAIN, he asked me to come to his office, where he explained that most soldiers never went on missions behind enemy lines, and he wanted the series to be about ordinary front line soldiers. So I followed orders and wrote about ordinary front line soldiers beginning with the second novel, HELL HARBOR.

en a Sergeant in WWII and participated in the liberation of Paris. After I handed in the first SERGEANT, which was DEATH TRAIN, he asked me to come to his office, where he explained that most soldiers never went on missions behind enemy lines, and he wanted the series to be about ordinary front line soldiers. So I followed orders and wrote about ordinary front line soldiers beginning with the second novel, HELL HARBOR. but even then I noticed that John Mackie and Gordon Davis sure described combat in very similar styles. I had never read anything like it. Maybe it’s nothing more than my own twisted psyche, but I consider you a genius at describing horrific carnage in a way that makes it sound rather fun. You’ve mentioned before your preoccupation with surviving a bayonet charge by the Red Chinese if you were sent to Korea—is that what got you started imagining such Technicolor bloodbaths?

but even then I noticed that John Mackie and Gordon Davis sure described combat in very similar styles. I had never read anything like it. Maybe it’s nothing more than my own twisted psyche, but I consider you a genius at describing horrific carnage in a way that makes it sound rather fun. You’ve mentioned before your preoccupation with surviving a bayonet charge by the Red Chinese if you were sent to Korea—is that what got you started imagining such Technicolor bloodbaths?