We took a tour of New Orleans, collecting from the various bookies. Each one paid us $400 in then-current denominations. With a net of $300 from each bet, we now had a couple thousand more than what we’d brought there.

We found our horseless coach where we’d left it, climbed in and shot a warp back to the hangar at BH Station. As we got out, Uncle Si handed me the stack of money and said, “And that’s one way to get yourself some seed money.”

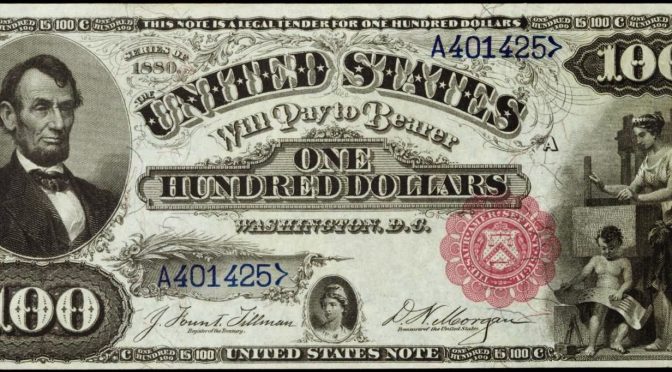

I flipped through the stack of bills, unbelieving.

“You could take that stake right there, buy up a bunch of real estate in Florida, and you’ll be a millionaire in the post-Disneyworld USA.”

As I examined one of the bills, I was reminded of what had bothered me before. “Uncle SI, why does it say, ‘the United States will pay to the bearer $100?’ If you’re the bearer, you already have $100. What’s gonna happen—they just trade you this hundred for another one?”

He chuckled and tapped his temple. “You’re sharp, Sprout. It’s good you notice these things, and question them. You should always be that way.”

I followed him back into the cool underground labrynthe and he explained on the way. He began by producing a bill from his own wallet and handing it to me.

“Compare those two,” he said. “Aside from the denomination and the design, what else is different?”

After I pointed out a few superficial differences he shook his head, made a cutting gesture, then pointed at the bottom of my bill.

“What does that say?”

“United States Note,” I replied.

Now he pointed toward the bottom of the bill he’d pulled from his wallet. “How about that one?”

“Federal Reserve Note,” I read, aloud.

He took his note back. “You don’t see anything on here about paying the bearer anything, either.” He flopped it around a bit before putting it back in his wallet. “Just some vague statement about it representing legal tender for all debts, public or private. This is what’s known as ‘fiat’ currency. It has no worth whatsoever, beyond durable fire kindling. It’s propped up only by assumptions, and the credibility of a government.”

He now pointed to my stack of money. “That’s not real money, either. It’s paper. The difference is: it doesn’t pretend to be real. Before it was replaced by funny money, you could take it to a bank and exchange it for real money—the amount of money printed on the note.”

I scratched my head. “Okay…then what is real money?”

“Gold or silver. That’s what a government backs paper currency with, if it’s honest, and not trying to screw the people. At your age it’s probably too much of a complicated, boring mess to be of much importance to you. But we’ll talk about it more when you’re older. Ultimately, the fate of the USA was settled by this very issue.”

***

We turned in our period clothing at the wardrobe and dressed comfortably again. Carmen fixed a meal for us, then we relaxed in the living room.

“So tell me what you learned on our field trip,” my uncle said.

“Well,” I said, “if you can travel through time, that means you know the future when you’re at earlier points in the time stream. You can make easy money when you know about what hasn’t happened yet.”

“Well said, Sprout. And now you know one of many reasons why history is important for you to know.”

“How many times had you seen that fight?”

“That was my first time.”

“B-but…” I stammered. “How…?”

“I’ve studied history,” he said, with a smirk. “I knew that Corbett won that fight.”

“But you knew more than that,” I protested. “A lot more. You were predicting what would happen, and when.”

He tapped his temple again—obviously one of his most common gestures. “Pattern recognition. I’ve got it. You’ve got it, too. That’s one reason why television bores you so much.”

“Especially sitcoms,” I said, reacting to his remark without considering how he knew this about me (we’d never talked about TV before).

“As you get older, it’ll help you out when you apply it to stuff beyond television, too. Important stuff.” He cleared his throat. “Of course, I’ve read a little about Sullivan, and a little about Corbett. Enough to make some deductions. The other part is, I know about fighting, and fighters. I’ve seen a whole lot of fights in my life. I’ve been in a few. That’s gonna become part of your training—watching fights. The more you do it, the more you’ll learn. When I first started, I didn’t understand much. I couldn’t tell when a man was hurt. I assumed the guy with the best physique was stronger and therefore would win. I didn’t understand why clinching was so effective. Actual real-life knockout punches didn’t look that impressive to me…partly because in Hollywood movies, guys get hit with freight train haymakers all the time…with bare knuckles, no less…and it hardly fazes them, unless some 98 pound chick throws it. Or unless the plot calls for it”

He opened a dark bottle of something and took a swig. “So what else?”

I replayed the “field trip” in my mind, briefly. “People couldn’t have been more wrong about the matchup,” I said. “It was completely backwards from how they thought it would go.”

He chuckled and leaned back in his seat, gaze roaming across the ceiling for a moment. “So much for ‘experts’—then and now. There’s some psychological factors at work, here. It can give you clues about human nature; and you can extrapolate from there into other situations. The sports writers who wrote all those articles you read? They probably saw Sullivan in action back when he was young, in shape, and hungry.”

“He sure didn’t look hungry when I saw him,” I said.

“That’s not the kind of hunger I’m talking about,” he said. “It has nothing to do with food. Once upon a time, Sullivan was hungry…probably starving…to prove himself. To make his mark in the world. To become a world champion. Then to stay champion. It made him very dangerous. He was a wild brawler, but was probably pretty good back in the day, relative to his contemporaries in the game. Remember that boxing was mostly illegal up until the fight we just saw, so there were social disincentives to get involved in it at all. There might have been somebody better during his own time—but if so, they didn’t fight him. Hell, Corbett himself might not have been able to keep out of range from the young, hungry John L. Sullivan.

“Anyway, that’s the Sullivan people remembered. When he wasn’t in a fight…and he’d been inactive for four years when he met Corbett…it was like he was invisible to the public at large. They didn’t realize he was becoming an alcoholic couch potato. They still remembered him as he was in his prime, and that’s who they expected to see again.

“In fact, they had probably exaggerated their own memories until he was better in their minds than he actually had been. There were 10,000 men in the audience, and most of them had never seen him fight before. All they knew about him was from exaggerated stories they’d heard—second or third-hand hearsay in a lot of cases, embellished at every telling. That’s why so many people assumed he was invincible.”

I nodded. This made sense, when I considered it this way.

“That sort of thing is a danger for everybody, to some extent,” he went on. “If you’re not careful, you’ll add to or take away from memories, until the actual truth is replaced by some more pleasing, or more convenient, modified version. Then you cling to your romanticized truth, and even if you’re reminded of the actual truth now and then, you’ve grown to like your version better, so you hang on to it and dismiss whatever disagrees.”

“That’s silly,” I said, laughing.

He shrugged. “Human nature is often silly. And what I just described is mild. Some people keep twisting and twisting the original data in their mind until they fall off the deep end. They can’t accept reality anymore because this fantasy they’ve concocted becomes their reality. And what’s even crazier is that groups of people…sometimes in the millions…can all adopt the same basic fantasy, insisting that it is truth and that their fantasy is the actual reality.”

I hadn’t yet witnessed this. Without experience or context, I couldn’t imagine it. I was sure Uncle Si knew what he was talking about, but the phenomenon had no more meaning or import to me than did the “West Coast Offense” during my life before picking up a football magazine in my mother’s favorite hair salon.

“What else?” he asked.

“What you’ve been teaching me about sudden violence,” I said, “it really works. It worked for me against the kids in the park. It worked for you against the guy with the handlebar mustache.”

He waved, as if shooing a fly. “That clown was no threat. Except to our ability to watch the bout. What else?”

“About Sullivan and Corbett?”

“Well, yeah. For starters. I’ll give you something to think about: what you saw there in New Orleans is the culmination of a pattern that has happened over and over again, and probably always will.”

I leaned forward and rested my chin on my fist.

“You see this especially in the Heavyweight Division of professional boxing,” he said. “Western boxing, that is. Some brawler comes along, and he’s a wrecking machine. He doesn’t just score knockouts on his way up the ranks, but he ends careers. His victories are so devastating, the victims are psychologically damaged afterwards. They’re beat so bad, it shakes their confidence. They’re never good enough to seriously contend again after a beat down from the Bad Boy. So finally, he slugs his way to the top. He is crowned champ, and in such convincing fashion that people assume he’s invincible. Including himself, sometimes.

“But then, now that he’s on top he gets complacent. Maybe because he believes the hype about himself, but also because there are no serious challengers now. None of the potential contenders have survived the mauling he dished out on his bloody climb to the top. So guess what happens?”

“He stops training?”

Si nodded, pleased with my answer. “Sure—in many cases. Or he stops taking his training seriously. Bottom line is, he gets soft physically at exactly the same time his ego goes out of control. What does overconfidence do?”

I recited what he taught me: “It leads to arrogance. Arrogance leads to recklessness. And recklessness leads to defeat.”

“That’s my man, Sprout. So while the Bad Boy is on his ego trip, up comes some fresh new guy, who wasn’t a victim of the bad boy’s rampage…maybe he hadn’t turned pro yet; was too young; inexperienced; whatever. But he climbs up the human rubble left over from that rampage, and next thing you know, he’s in position for a title bid.”

“And nobody takes him seriously?”

“Of course not! Not in a fight against the Bad Boy. The Bad Boy is invincible!”

I laughed at this.

He knocked back another shot of booze. “Let’s call this guy ‘the Challenger.’ Y’know, I can think of one time when he wasn’t even all that good, but the result was the same.”

“Big upset? New champion?”

He nodded. “That’s right. Every single time. Well…I take that back. There’s one exception in the history of western boxing: Marciano. The Rock never got complacent; never slacked off on his training; never stepped through the ropes without bad intentions…until retiring undefeated as a professional. And he stayed retired.”

“I think I’ve heard of him,” I said.

“But like I said: the Rock is the exception. The only exception to this pattern.”

“So the same thing happened to Corbett?” I asked.

He grimaced. “Not exactly. Corbett was never a wrecking machine, so he doesn’t fit the pattern, anyway. Still…there are similarities. After he became champ, he got lazy. Starred in a Broadway play about himself instead of defending his title.”

“And along came the Challenger!” I crowed, proud of how clairvoyant I was.

“Bob Fitzsimmons,” my uncle said, nodding. “A blacksmith by trade, so he had pretty good upper body strength. Looked like a heavyweight from the waist up, but skinny little birdie legs. He was actually a middleweight, if memory serves. Tough son of a bitch, too, I’m guessing.

“So he gets a title shot. Gentleman Jim isn’t at his best, but he hasn’t fallen apart, either. I forget how many rounds they go, and Corbett just makes him look stupid. But Fitz isn’t out of shape and over the hill like Sullivan was. He’s game, and waits for his puncher’s chance.”

“I guess he got it,” I surmised.

“Yup. And a body shot, at that. Sports wags called it ‘The Battle of the Solar Plexus.’ Knocked the wind out of Corbett. Gentleman Jim couldn’t beat the count. New champ.”

“The solar plexus—where’s that?”

He reached over and gently pushed his fist against the center of my torso just under the sternum.

“Pit of the stomach. You take a big shot there, it can paralyze you for a minute or so. It’s one of those nerve centers I’ll teach you about down the road. There’s another one in your ass. Anybody ever literally kicks your ass…I mean between the cheeks and up into the hind part of your crotch…it hurts like a blind mother. I mean pain like high voltage chainsaws ripping all through your body.”

I knew what he was talking about. Allyson had kicked me there when I was six years old. The pain was crippling. She made fun of me for crying, but I couldn’t stop.

“So what else did you learn?” he asked.

I thought some more before answering. “Corbett’s technique had flaws. His punches were sloppy—lousy form, and sometimes he telegraphed, too. It’s just that Sullivan couldn’t slip or block them, anyway.”

“So what does that teach you?” He fixed me with a piercing gaze.

“Perfection isn’t necessary to win,” I said. “Sometimes mediocrity is enough.”

He scared me by jumping to his feet and whooping, his bottle held high over his head. “Helmuth Von Moltke the Elder! Outstanding!”

Carmen entered the room to see what all the noise was about. He pulled her into an embrace and covered her mouth with his. I turned away as they seemed to be trying to eat each other. But then he pulled away, Carmen’s lipstick now smeared all around his mouth, and pointed at me. “That is one sharp young man, right there! What’re we gonna do with him?”

What he would do with me, it turned out, was test me to see if I could put what I knew to use.